Stories

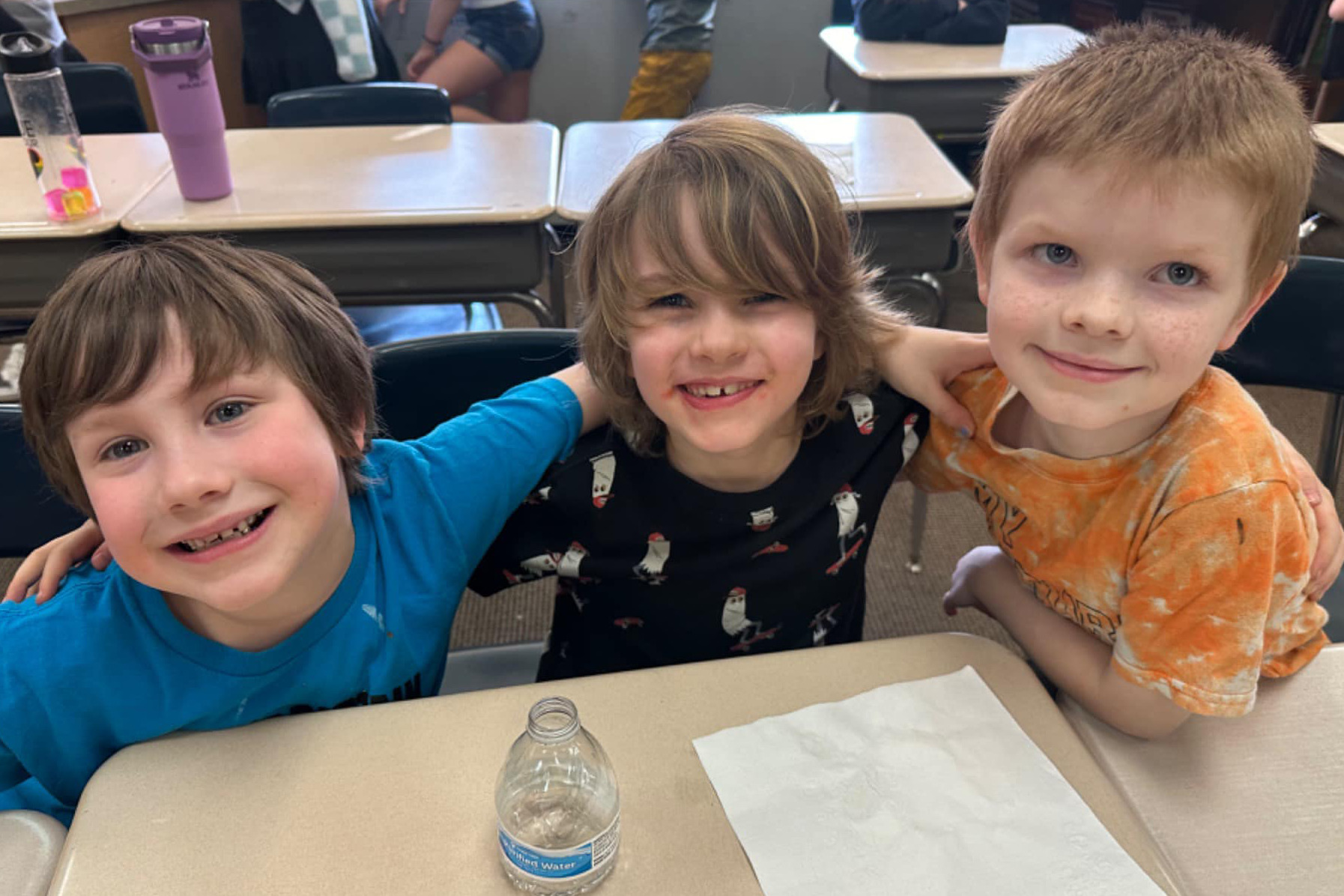

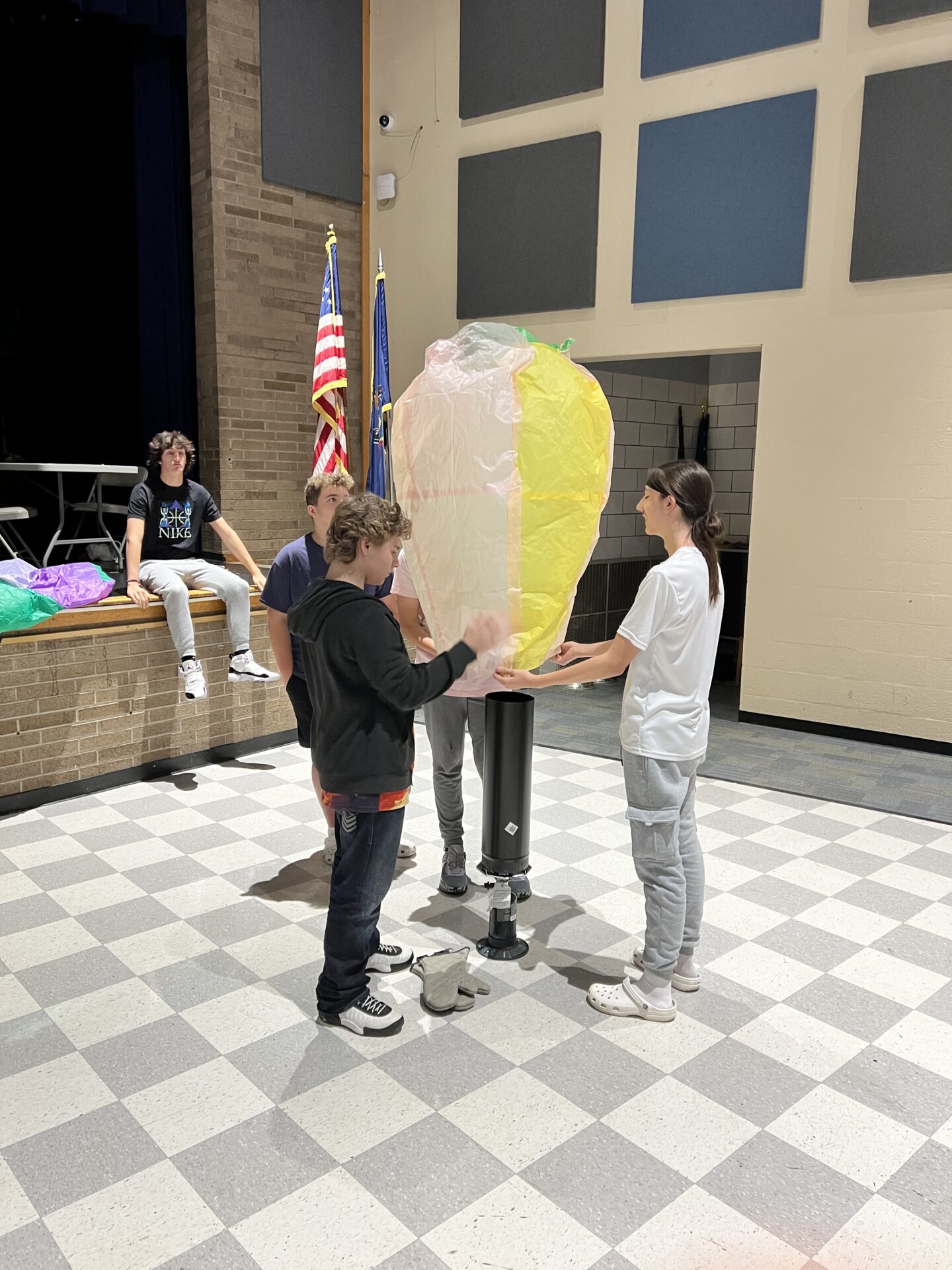

TEACHING AND LEARNING POST-COVID

With the lifting of the national emergency order this May, it’s clear we’ve reached a new phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. What does that mean for teaching and learning?