In June, high school bleachers and auditorium seats will fill with parents and grandparents. Seated shoulder to shoulder, they will watch their teenagers accept freshly minted diplomas. Names will be announced. Family members will cheer. Then the hugs and mask-free celebrating will commence.

The canceled graduations and socially-distanced celebrations of three years ago are a memory now. Yet it’s hard to know what to call our current moment. The words “post-pandemic” still feel overconfident, as though we’re challenging some new COVID variant to rise up and surprise us. But clearly we’ve reached a new phase.

By the time this school year ends, the state of national emergency will have been lifted. The COVID virus is no longer keeping educators and students from gathering in classrooms and out-of-school-time spaces.

So where does that leave us, three years after the onset of the most widespread disruption to American life that most of us can recall? In particular, what have educators learned from their experience teaching and caring for students, their families and their communities over the past three years?

At the height of lockdown, educators were already looking ahead and asking what good could be mined from the crisis. Teachers and administrators spoke passionately about seizing the moment and not returning to a pre-pandemic “normal” that hadn’t been serving many of the region’s children anyway.

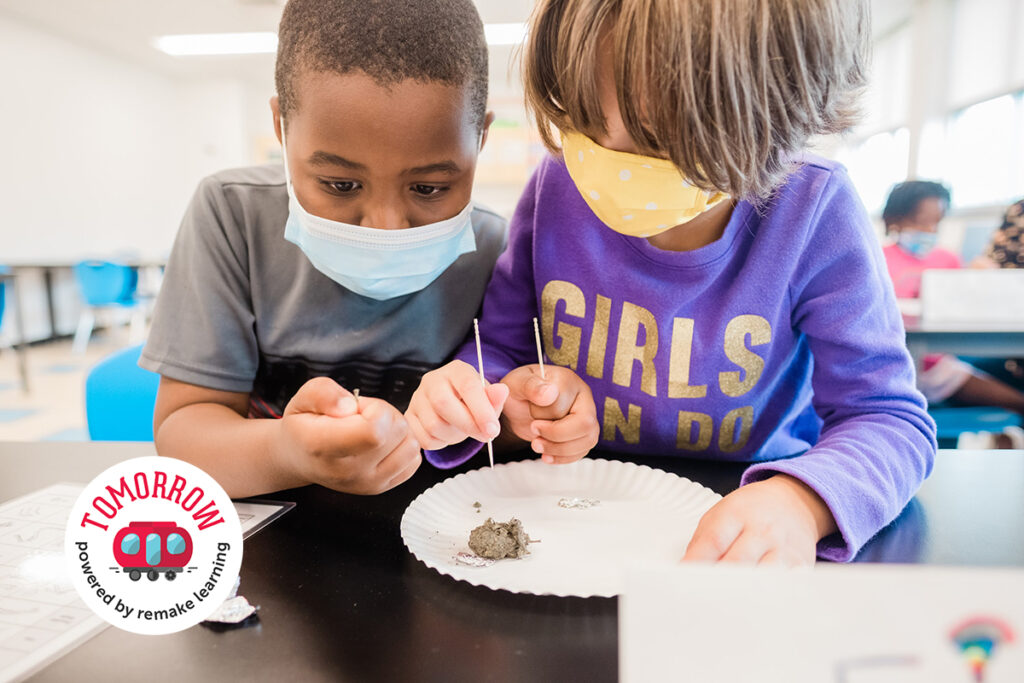

During those first disrupted months, educators hacked the process of teaching and learning. Traditional tests were replaced with alternative assessments. Learning happened everywhere. Parents were participating in the learning process in new and powerful ways.

Even as a degree of normalcy returned in the fall of 2020, the calls for innovation continued.

“In our district, we’ve been talking about not just getting back to normal, but getting back to better,” Baldwin-Whitehall Superintendent Dr. Randal Lutz told the audience during an October 2020 back-to-school webinar titled “Transform for Tomorrow: What’s working in schools now?”

The refrain was constant: We’re making valuable discoveries about what learning can actually look like. Let’s not lose the lessons.

DISCOVERIES AND MINDSET SHIFTS

The new “normal” involved more than just innovative approaches to teaching and assessments. In school districts throughout the Pittsburgh region, the role of educators was growing. Mental well-being and social-emotional learning emerged as priorities in many school districts and out-of-school-time programs.

The “Remaking Tomorrow” report, released in the summer of 2020, noted “every caregiver’s essential role as an educator and every educator’s undeniable role as a caregiver.” Relationships took center stage.

“We found that our duty as educators wasn’t just around the academics,” says Vicky Hsieh, director of innovation at Environmental Charter School (ECS). “We had to also help facilitate some of those social aspects.”

In the early days of virtual learning, “we did this ‘virtual adventure’ for the first three or four weeks of school instead of diving right into traditional academics,” Hsieh says. “It was around understanding your learning identity, building your own schedule, executive functioning.”

The disruption was treated as a challenge: How can you find math tools within your house? How can you navigate your big emotions as we all get through this pandemic together?

“Families were really impacted by not having the social elements for their children. So we embedded into the schedule a lot more social opportunities,” Hsieh says. Lunchtime included virtual dance parties. Families and teachers met up outdoors for safely distanced hikes.

Relationships were also central at Homewood Children’s Village (HCV), where staff members were busy operating a Learning Hub for local kids,

“We’ve always looked at it as holistic work – the whole child,” says HCV’s president and CEO, Walter Lewis. But HCV team began having deeper conversations with families about their children’s education and how the organization might support learners in ways they’d never considered before.

“There were a lot of families that said that they were interested in homeschooling,” Lewis says. “They weren’t feeling like their children were benefiting most from their current educational situation.”

Those conversations grew into planning sessions: What might it look like if HCV helped out somehow? After the herculean effort of getting thousands of meals to families in the early months of the pandemic and the successful operation of HCV’s bustling learning hub, it was easier to dream big.

“We learned that we can do a lot more than we think we can. And we can move more quickly than we sometimes think we can,” Lewis says. “We do have the capacity to come together and do amazing things.”

Another discovery that rippled out across the Pittsburgh region: “Learning happens everywhere” is much more than a catchy expression. It’s a workable reality. And exploring new ways to put it into practice benefits everyone.

THE PUSH-PULL OF REOPENING

It was thrilling when classmates and their teachers could finally occupy the same space once again. And as in-person learning resumed, folks were driven to continue working on innovative projects. At the same time, though, there was a powerful and understandable yearning for the comfort of familiar things.

“There was a lot of reverting back to normal, and so we actually saw the pendulum swing back to very traditional learning,” Hsieh says. “It’s human nature. You revert back to normal when you’re exhausted.”

At ECS, there was a lot of listening to stakeholders and reflection on what should carry forward. Much of the momentum came from kids: “They were pushing back on the ways that we used to be, because they didn’t work,” Hsieh says.

Early in the pandemic, ECS had leaned into listening – hosting dialogues with parents instead of traditional parent-teacher conferences. More recently, as they tackled their new strategic plan, ECS returned to that approach, asking stakeholders and communities about their sense of belonging and identity, and about feelings of agency and empowerment in school.

ECS has also begun reshaping independent and group projects to give students more agency and more opportunity to connect with one another.

For example: Ninth-graders design outdoor adventures in partnership with Venture Outdoors that can include things like kayaking, biking and fishing. But it adds more requirements that focus on teamwork; they have to navigate and decide as a crew on a plan.

“A lot of our students came back and were like, ‘This didn’t feel like learning. This didn’t feel like school. This felt like this was a bonding time,’” Hsieh says. “And we’re like, ‘Yeah, because that is part of learning.’”

Local organizations also work with ECS to design workshops that bring students out into the community, connecting them with experts and planting seeds for ongoing mentorship. When students return to school, they examine their experiences so that it doesn’t become just a field trip.

“They’re actually reflecting on the process, and then connecting it to themselves to be able to articulate how they’ve learned more about their identity,” she says, “and how they want to contribute that to their community and the world.”

And rather than one-off experiences, these workshops now form a high school course.

Another way that early pandemic discoveries have led to post-pandemic growth at ECS: That “virtual adventure” that students experienced before remote academic learning began has returned in a new form. Intermediate and middle school students now kick off the year with a four-week primer around culture-building, identity and other “social-emotional pieces,” Hsieh says.

Teachers requested this shift, because “by slowing down and listening to your students and helping them understand who they are as learners, that is going to help you as an educator to build relationships,” Hsieh says.

This culture-building experience has now become a year-long seminar class for sixth-graders.

PROGRESS TAKES HOLD

At the Homewood Children’s Village, the experience of operating an emergency learning hub during the pandemic led to powerful discoveries – and growth that Lewis hopes will be permanent.

During the early days of the Learning Hubs, HCV staff had a curious experience as they stood by while students struggled with virtual classes.

“You’re so close to the learning. You’re almost like a fly on the wall, watching learning take place but not being able to do anything about it,” Lewis says. “You can see children who are struggling, who are not learning the material, but there isn’t really a place for you to insert yourself.”

Hosting kids from multiple grades and multiple schools made it “difficult to create an environment where you can address each of the individual needs,” he says. “We created environments where the kids felt safe, where they felt loved, cared for, all of that kind of stuff. But we had minimal impact on the actual academic side of things.”

That led to the creation of HCV’s Village Learning Hub, a virtual menu of services and resources that supports a growing pool of homeschooling families in Homewood.

The Village Learning Hub helps in a range of ways:

- COMMUNITY/CONNECTION: Giving homeschooled kids regular access to social interaction and group learning with other children.

- LEARNING PLAN ASSISTANCE: The challenge of creating a state-approved learning plan is a hurdle that can keep parents from pursuing homeschooling, especially if they have no personal experience with teaching. HCV has hired several educators to help parents build, evaluate and certify their Learning Plans.

- PHYSICAL SPACE: HCV doesn’t have a big building where homeschooling families can gather, Lewis says. What it does have is committed partners and access to physical space. So the Village Learning Hub connects families with libraries, local community centers and other places where they can meet for play experiences, take classes and seek tutoring.

- ENRICHMENT SUPPORT: HCV runs a Community Schools Initiative connecting kids from Pittsburgh Westinghouse, Faison and Lincoln to out-of-school-time enrichment and care. They’ve now begun pointing homeschooling parents to the same resources.

These kinds of pandemic-era discoveries are taking root throughout the Pittsburgh region.

The growing focus on parent-school engagement has led to the launch of the Parents as Allies research initiative, which is sparking deeper connections at dozens of school districts.

From Northgate to Clairton City and so many districts in between, new levels of social-emotional learning and mental health support are becoming permanent pillars of learning.

At California Area School District, animal-assisted learning is supporting school-wide mental health. At Allegheny Valley School District and Frazier School District, new spaces are being created where students can decompress and build valuable coping skills.

And at schools and out-of-school-time programs throughout the Pittsburgh region, there have also been powerful mindset shifts and an increased focus on social-emotional learning.

“We have found that our students, especially our adolescents coming back, they really need help understanding … themselves,” Hsieh says. “It’s more than just having more therapists and social workers and more counselors. Across the board, we collectively need to have a mindset where we are helping our students have a sense of self and understanding of others.”

Among the biggest mindset shifts echoing throughout the region: As we care for kids, the well-being of educators must also be a priority.

“We cannot expect our educators to be the only ones holding all the weight of this,” Hseih says.

ECS, like so many schools, has worked with Awaken Pittsburgh to share trauma-informed teaching techniques and also to give teachers their own space to address the trauma they’ve experienced.

“When we have the adults in a school being rejuvenated, being supported and being taught self care, and helping them with their own compassion fatigue and burnout, that’s when we see their batteries recharged,” says Awaken Pittsburgh founder Stephanie Romero. “Because it is a tough job, right? It is a really tough job.”