On the night of graduation, a ceremony that usually caps the collective achievements of a community, David McDonald, the superintendent of South Allegheny School District, had a moment of terrifying clarity.

“I realized we were failing kids,” McDonald recalled.

“I was asking kids after the ceremony, ‘OK, what’s next?’ And every time a student said, ‘I don’t know,’ it was like a gut punch. We had kids who had no idea what they were going to do.”

At South Allegheny School District, home to 1,500 students, about 50 percent of graduating seniors matriculate to college. The rest are bound for the workforce. Honoring that reality was critically important to McDonald, who was concerned the District was not adequately preparing graduates.

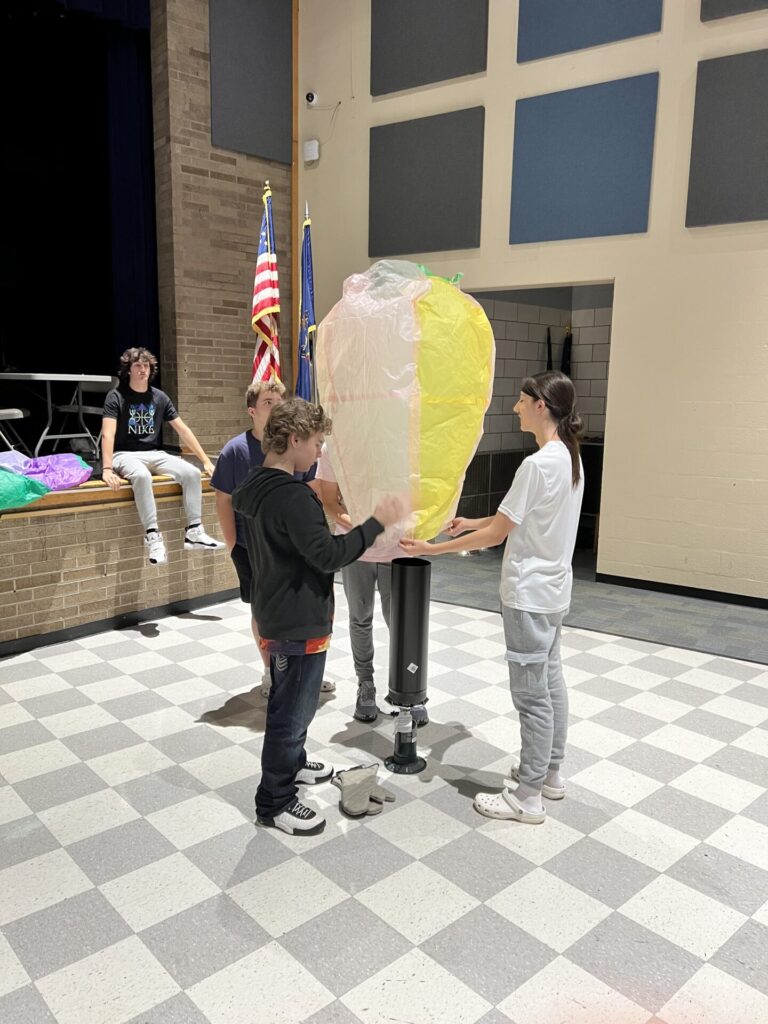

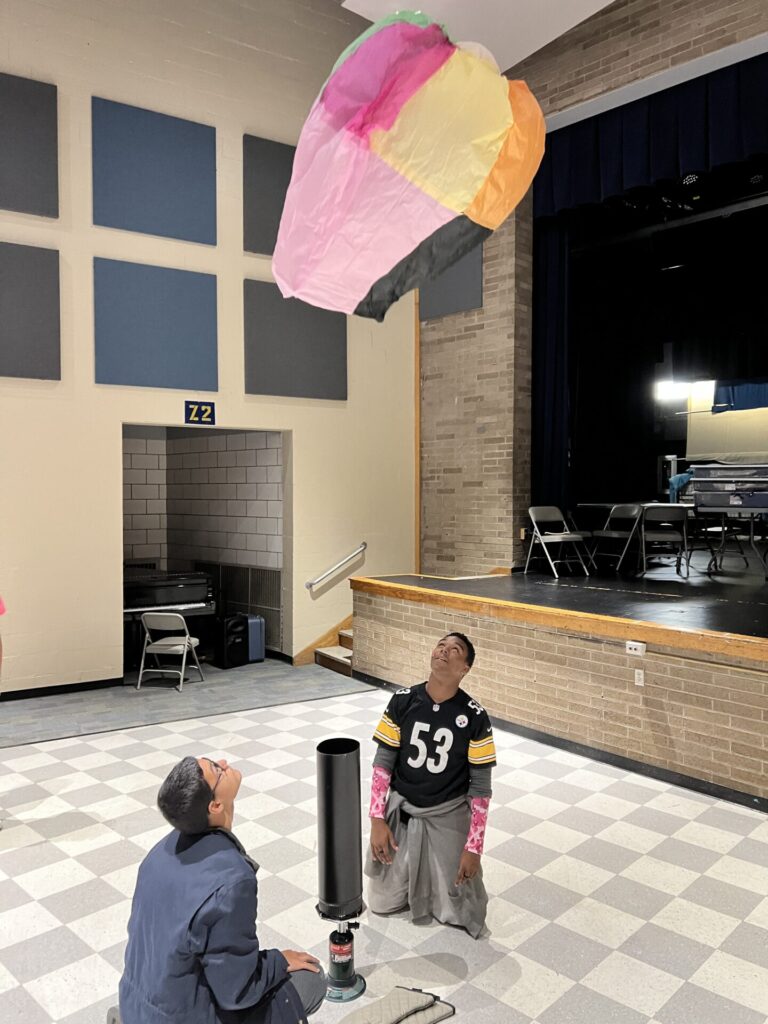

After that June evening two years ago, McDonald and his team got serious about making deep changes. With a focus on personalized learning to drive relevant, real-world learning opportunities, South Allegheny flipped the schedule of the District’s high school, giving students a daily 90-minute personalization period, known as “flex,” to try out different subjects and pathways.

Every day during flex time, students opt-in to join typical classes like literature, math and science. They can also explore aviation, cyber security, leadership, tutoring, chess and recycling or kindness club, to name a few. Educators have flexibility to co-develop courses with students to match their hobbies and interests, a strategy that has improved engagement and culture school-wide.

Notably, the District embedded courses that are generally reserved for after-school hours into the school day, reducing a significant barrier for students who have outside responsibilities. That switch gives the entire student body access to creative learning and extracurriculars.

“Seventy percent of our District is economically disadvantaged,” McDonald said. “We have a huge population of kids who are going to work after school, or taking care of a family member, so it was important to provide traditional after-school opportunities during the school day.”

McDonald’s team also designed rigorous workforce programs, called Academies, to expose students to skills that are relevant and marketable. The first, Aviation Academy, was launched with support from a Remake Learning Moonshot Grant, which allowed South Allegheny to purchase a flight simulator. They now have four, with distinct pathways that can lead to in-demand jobs like earning a pilot’s license or becoming an airline mechanic.

“Our goal here is to provide students with the knowledge and inspiration to be aware of the opportunities that exist in the aviation field, which has plenty of high-paying jobs,” said Tim Rishel, a South Allegheny teacher who leads the program. As a kid, Rishel was always passionate about flight, but he didn’t know the route to “get there,” — a knowledge gap he is purposefully filling for students like 18-year-old Dante Saputo.

“Aviation was never a pathway I considered, but getting to be in this class, there’s so many ways it’s intertwined with history,” said Saputo, who was absorbed by aviation’s long historical arch. “From the early Greeks up to modern jet engines, people have been fantasizing about flight,” he added.

Kayla McEwen, 17, agreed with her classmate. “I like everything about this class.” she said. “I was the first student who used the flight simulator, and it was so amazing.”

The District is one of only a handful of Pennsylvania schools using the national Aircraft Owners andPilots Association curriculum, with a goal of developing trade school partnerships that give students a solid “head start,” earning transferable credits that can be applied toward industry-recognized certifications.

“You Can’t Be What You Don’t See”

South Allegheny has embraced multiple strategies to propel students forward, including an emphasis on real-world exposure and personalized learning, which creates authentic, equitable learning opportunities centered around each learner’s strengths, needs and interests.

The District also dedicated a longtime teacher, Laura Thomson, to serve as the high school’s workforce coordinator, helping students identify possible career paths and connect with them in hands-on ways.

“A student can’t be what they don’t see,” said Thomson, who takes students to trade conventions, union halls, job sites, hospitals, the Pittsburgh Zoo — any accessible workplace that piques their interest.

“It’s really hard to talk to a student about being an ironworker, or a steamfitter, or a carpenter when they don’t see exactly what that job is and use the tools that you would use in the environment,” she added.

The District is focused on opening doors to entry-level pathways that offer health care, pensions, and wages that can support a family and homeownership.

“We’re talking about real life personalization for kids,” McDonald said. “We want to give them exposure — academically, socially, emotionally, and from a workforce standpoint, we’re giving them multiple lanes to learn concepts that apply to real jobs.”

South Allegheny is one of two school districts in the country to offer CompTIA certifications, a cyber security pathway that starts with a “training ground” for seventh and eighth grade students who can later matriculate to the skill-based Academy in ninth grade.

“When students complete our program in four years, they are prepared to go onto multiple academic tracks, but they are also prepared for the workforce and have all the skills to walk into a cyber security job,” McDonald said.

That matters in South Allegheny, a community deep in the Mon Valley that was once home to tube and steel pipe mills — and an abundance of blue-collar jobs that are now gone.

“We do a lot with a little, because we don’t have a great tax base,” McDonald acknowledged. “We’re old-school western Pennsylvania.”

In the Rust Belt, the residual effects of industrial decline are omnipresent; only 20 percent of South Allegheny’s residents hold bachelor’s degrees, and lucrative jobs are scarce. With the welfare of the larger community in mind, the District has plans to open an adult workforce academy to flip the economic standing of the region.

“If we could train 20 parents a year and expose them to higher-paying cyber security jobs, that’s going to be a game changer,” McDonald said. “Instead of just surviving, we want our students and families to thrive.”

Author: Erin Kane