Ask participants in Oasis Farm & Fishery’s Learning Village Model what the project offers and you may hear a dozen different answers. They will all be accurate.

It’s about learning to grow healthy food in an urban neighborhood. It’s about understanding how food deserts come about, and diving deep into the nutritional differences between packaged foods and fresh produce. It’s about the realities of running a restaurant or a food truck, and about the urgent need for a healthy ecological environment.

It’s about learning in formal and informal settings, with the needs of Black and low-income students centered and the voices of community elders and the history of Black foodways celebrated. It’s about cultivating relationships among community members and participating organizations. And it’s about preparing students for meaningful careers and healthy lives, and supporting their parents’ aspirations as well.

It’s about putting good food on tables today, and building leadership skills for tomorrow. More than anything, it’s about giving young learners and their families the skills to build a truly just and thriving future for the Pittsburgh community of Homewood.

And yet, even as the Learning Village Model has celebrated local knowledge and literally planted roots within Homewood’s local soil, it’s a model that can be applied in communities throughout the world.

Even in urban neighborhoods with few patches of open land, young people can learn urban farming and embrace cooking fresh food and begin advocating for healthier lives for themselves and their families, and learn about their cultural history in new and powerful ways.

Who

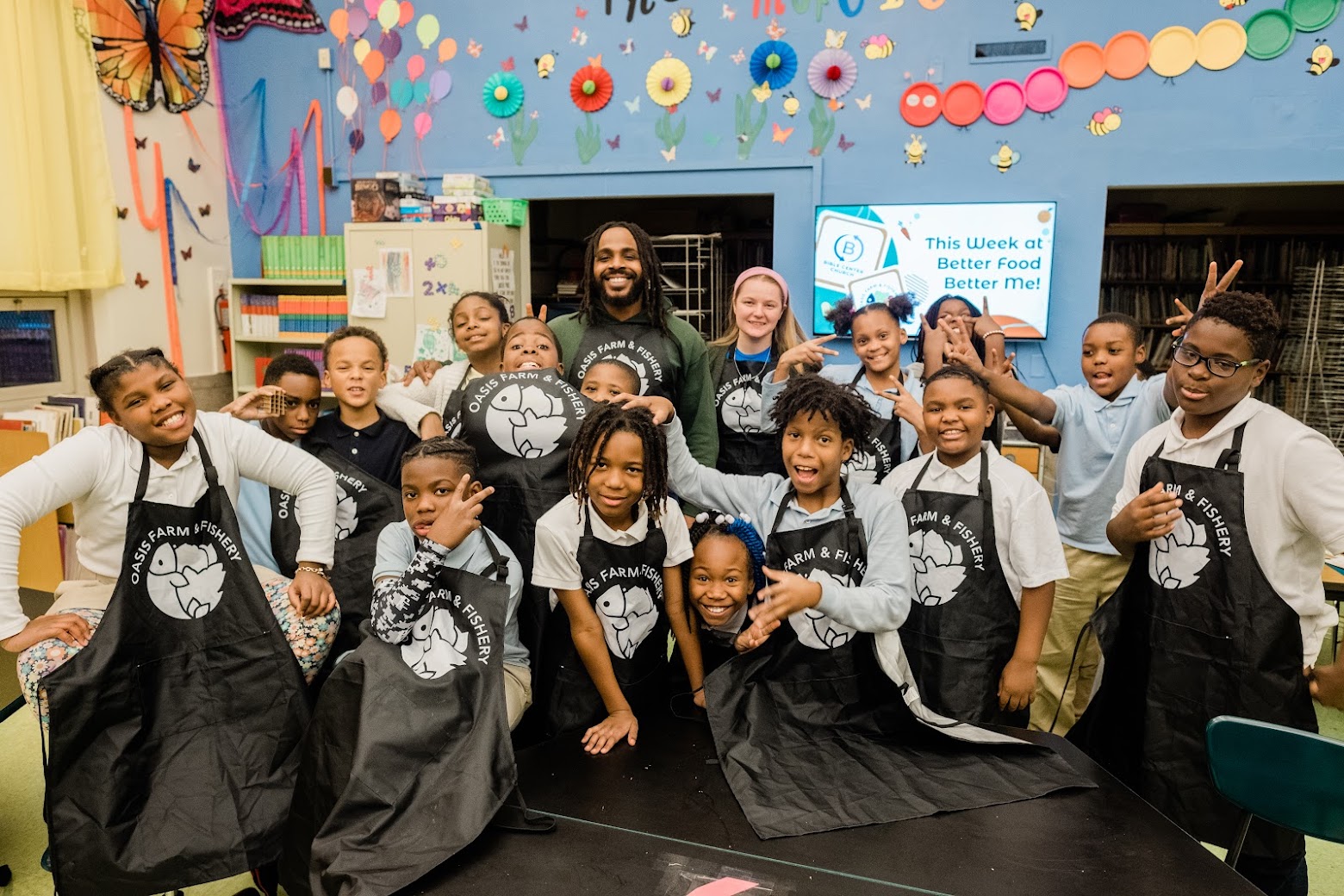

As the name suggests, there was an entire village involved in this work. Two local youth service providers – The Maker’s Clubhouse at Bible Center Church, which is the home of Oasis Farm & Fishery, and Operation Better Block’s Junior Green Corps initiative – worked with local agricultural experts, university staff and other adults from around the Homewood community, and with teachers from Environmental Charter School, Chatham K-12’s Environ-mentors program and Westinghouse Academy.

The Oasis team didn’t want to duplicate the work of other community organizations and they sought partners who could facilitate programming with their target stakeholders – students living in and around the Homewood area — throughout the school year.

They knew it was important to connect with the right partners to really knit together an active village that would support students and their families in environmental learning, building agricultural and cooking skills, and so much more. So they were purposeful.

“It’s about relationships and establishing trust,” says Tacumba Turner, who led this project on behalf of Oasis Farm & Fishery. “That’s the work ahead of time.”

It’s important to have a clear sense of what potential partners are currently doing, and how and whether a collaboration would be beneficial, he says. It’s also important to connect with multiple people at a partner organization and ensure that you all share the same vision, because turnover at nonprofits can be quite high.

That connecting, he says, “is not just tangential” and doesn’t just happen at the beginning. Relationship-building is a central pillar of the Learning Village Model.

And just as a village contains people of all ages, the Learning Village Model (LVM) serves a broad range of learners, from 6-year-old children all the way up to 60-year-old grandparents. Pockets of learning happened everywhere, with many participants. One group of high schoolers embraced the workforce development aspect of this project, but their learning went far beyond career training.

Each week, the LVM staff designated time to explore aspects of wellness: physical, emotional, intellectual, social, environmental, financial and occupational. This included field trips and visits (including virtual ones) from experts, and plenty of debate and conversation.

Why

Junior Green Corps and Oasis Farm & Fishery share common goals:

- To teach agricultural and ecological skills that prepare young people to explore what are called “green-collar” jobs and careers.

- To teach leadership skills that prepare young people to better the future of their community.

Those goals formed the beginnings of this project. But Turner and his collaborating partners brought the voices of the community into their planning from the very beginning.

They canvassed the community on foot, asking their neighbors about their concerns and desires for their community. They asked about the built environment itself and about the social environment. More than 200 people responded, and their words revealed a deep sense of pride and nostalgia, along with a powerful desire to see Homewood become a safer and more prominent neighborhood within the context of Pittsburgh.

Through this community-driven design process, they made plans to create The Nook, which is now growing into an intergenerational, outdoor educational space filled with garden beds, trees, and flowers, where residents of Homewood can learn about and grow plants while connecting with one another.

The Nook is a physical example of the preferred future that this project is working towards: By providing a robust “green” education to residents of all ages, and offering the physical space and opportunity to use that knowledge, the project aims to prepare students for meaningful careers and healthy lives in a community that fosters intergenerational learning among families of color.

What

These projects have varied in scope and in participants.

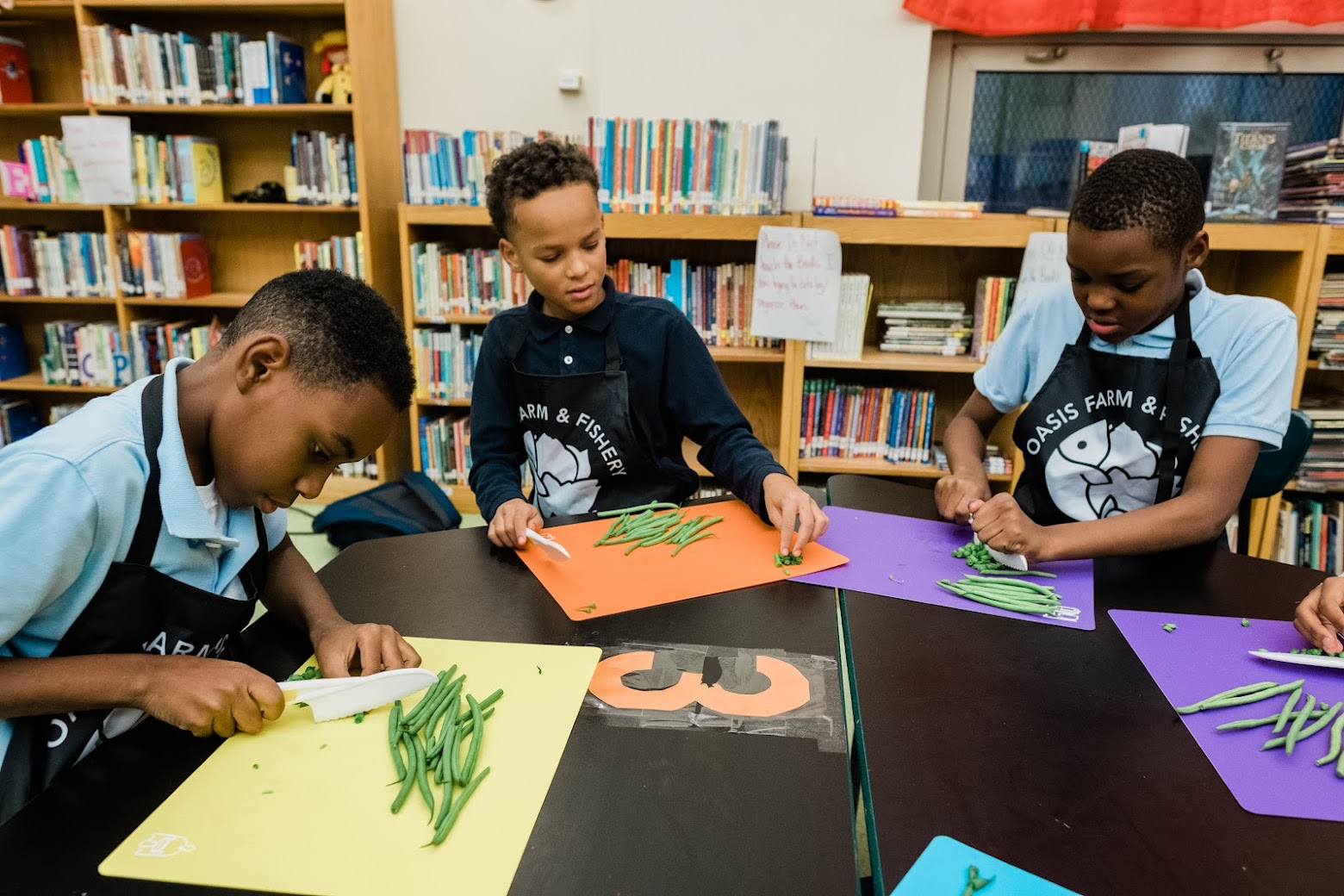

Work with students has included a program with teens at Environmental Charter School (ECS) that explored food-based learning and its connection to so many aspects of day-to-day life, while also connecting food to the periodic table and the scientific method.

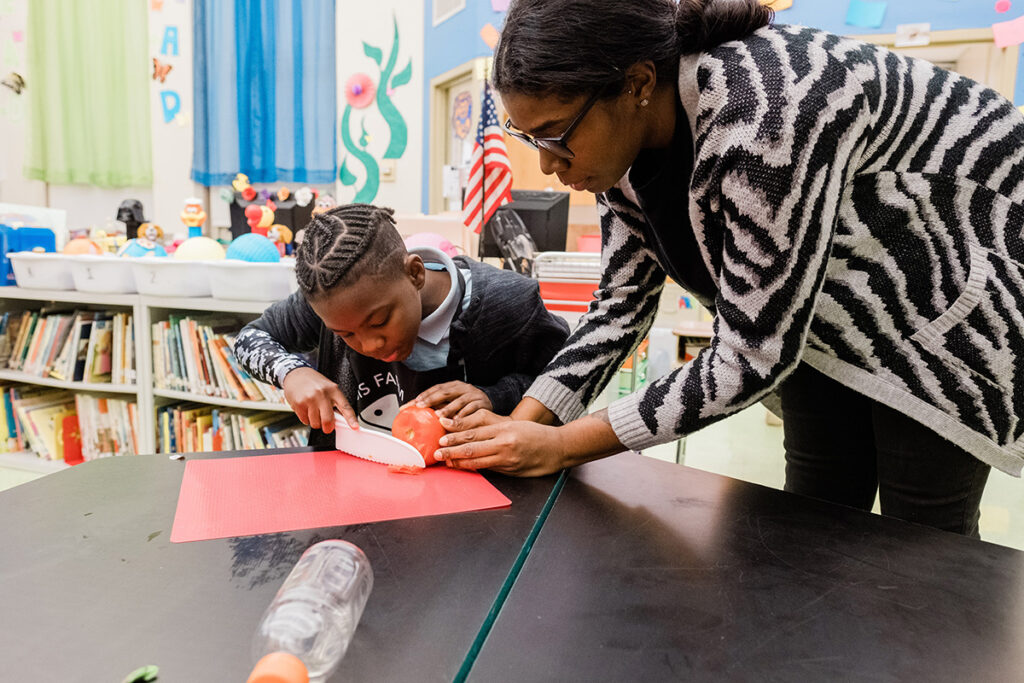

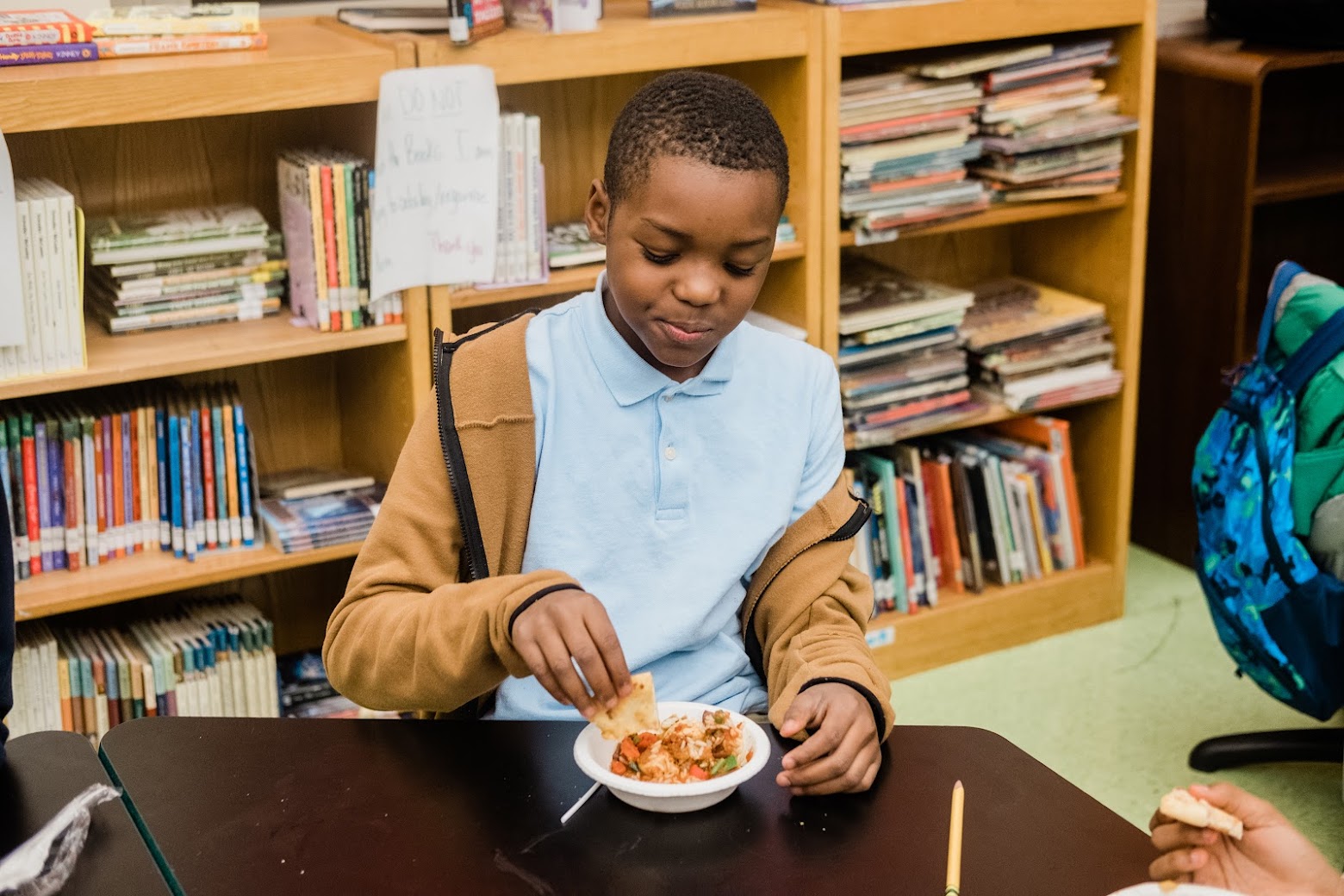

A group of second-graders completed a cooking class that explored where food comes from, how it’s grown, and what nutrition is all about. As they introduced these young learners to food literacy and ecology, the classroom teachers became more curious about health and food systems, and about integrating garden education into the curriculum in the future.

Longer-form learning modules like these allowed for nuance and exploration, and gave students a deeper understanding of the environment and systemic issues around food.

But shorter workshops were also powerful. One adult workshop, titled Food For The Culture, honored what community members already knew while creating space for new learning and for wellness check-ins. Parents experimented with healthy recipes to make for their children, and forged connections with one another in the process.

Shifts

Turner and his team saw positive changes in attitude, knowledge, and sense of self-efficacy within their community. Civic engagement increased and older adults began expressing enthusiasm around growing vegetables and incorporating more vegetables into their diet.

Faculty members at ECS are becoming conduits of change within their school as they begin seeking out novel experiential learning opportunities. Oasis and ECS are now discussing plans for year-round programming with 7th to 10th graders.

Two youth apprentices who worked as part-time farm assistants found the experience so inspiring that they’re now curious about pursuing “green” careers. Many more children are discovering the possible career paths within environmental work and agricultural work.

Students were able to bring home knowledge of food and cooking, and connect their parents to resources like the fresh food grown at Oasis, which has given those families an increased capacity to make and enjoy healthy meals at home.

The physical environment in Homewood has changed. The farm spaces are more vibrant and neighbors from all over Homewood are attracted to this vibrancy and activity. Community members are enjoying the beauty that they’ve collectively built, and are embracing this local, relational source for some of their favorite foods.

Why It’s Working

Relationships were a priority from the start – not just between the partnering organizations but also between the project organizers and the learners. The organizers paid attention to the holistic experience of youth working on the farm, and created conditions for excitement. They included content on racial justice as a foundation. They made sure hard work was mixed with plenty of laughter, and they got to know the students as individuals.

Building on the concept that participation in cohorts can jumpstart curiosity in learners of all ages, a spirit of community infused the entire project. “Many participants have called this fellowship,” the organizers wrote in a report about the project. “It’s been profound and healing for folks in our neighborhood to reconnect and see one another on the same journey.”

Barriers Encountered

The organizers encountered what they called “a general layer of cynicism about enacting enduring change.” And they ran up against the unavoidable time constraints faced by a neighborhood of people who work long hours. So while they knew they were offering valuable learning experiences, it was harder than expected to recruit large numbers of participants.

When learning took place inside classrooms, there was a limit to what students could explore and experience. This work happened most effectively in kitchens and outdoor farming spaces where hands-on, experiential learning was possible.

Staff turnover at some potential partner organizations meant that a few potential partnerships didn’t develop.

Children as young as second grade had what the organizers call “uncritically absorbed ideas about how Black communities experience environmental injustice, or that they ‘don’t’ or ‘shouldn’t’ garden, or eat certain kinds of foods.”

Advice From This Project for Like-Minded Efforts

Some learning goals are best achieved through a wide range of approaches. Rather than zeroing in on one approach – like formal in-school learning, out -of-school-time internships or single-evening workshops – the answer may be to use a range of approaches, all with a common goal.

Even when you’re offering beneficial learning opportunities, it may be necessary to also offer incentives (vouchers, stipends, or honorarium) to enhance participation.

Relationships – among those doing this work and with those being served – are the most fundamental key to success.

Connecting with kids in classrooms is meaningful, but creating true “green leaders” of tomorrow requires working with them in kitchens and gardens.

Authored by

Melissa Rayworth

Melissa Rayworth has spent two decades writing about the building blocks of modern life — how we design our homes, raise our children and care for elderly family members, how we interact with pop culture in our marketing-saturated society, and how our culture tackles (and avoids) issues of social justice and the environment.