As the only high school guidance counselor for the small community of Clairton, Maureen Shaw knows her students. She communicates with their families. She’s aware of the trauma they face—the pressures of poverty and social injustice, and all the instability those circumstances can bring.

She knows that these teens need support that they often don’t receive.

Shaw has been at Clairton City School District for 17 years—the entire lifetime of the high schoolers she now counsels. Along the way, she’s gotten to know the adults working in her district, and she knows they need support, too. The pandemic only made life more stressful for teachers in small districts with limited funds.

Clairton lies just 15 miles south of the increasingly revitalized city of Pittsburgh. But the surrounding hills seem to isolate this community where the economic shock of the steel industry’s decline still reverberates.

When Shaw came across a 2020 study by the Black Girls Equity Alliance, the worrisome data it revealed was all too familiar: Pittsburgh, the study found, refers more youth into the juvenile justice system than 95% of cities its size. And those referrals are even more racially disproportionate in Pittsburgh than in other cities.

The study recommends that schools hire counselors and psychologists, and train educators to offer culturally-responsive social-emotional learning. Instead of criminalizing students’ behavior, isn’t it better to offer these children mental health support and the behavioral skills they need to manage their challenging lives?

That all made perfect sense to Shaw. She could imagine a future where all students and staff would have their behavioral health needs addressed through prevention and intervention, effectively dismantling major barriers to learning and growth.

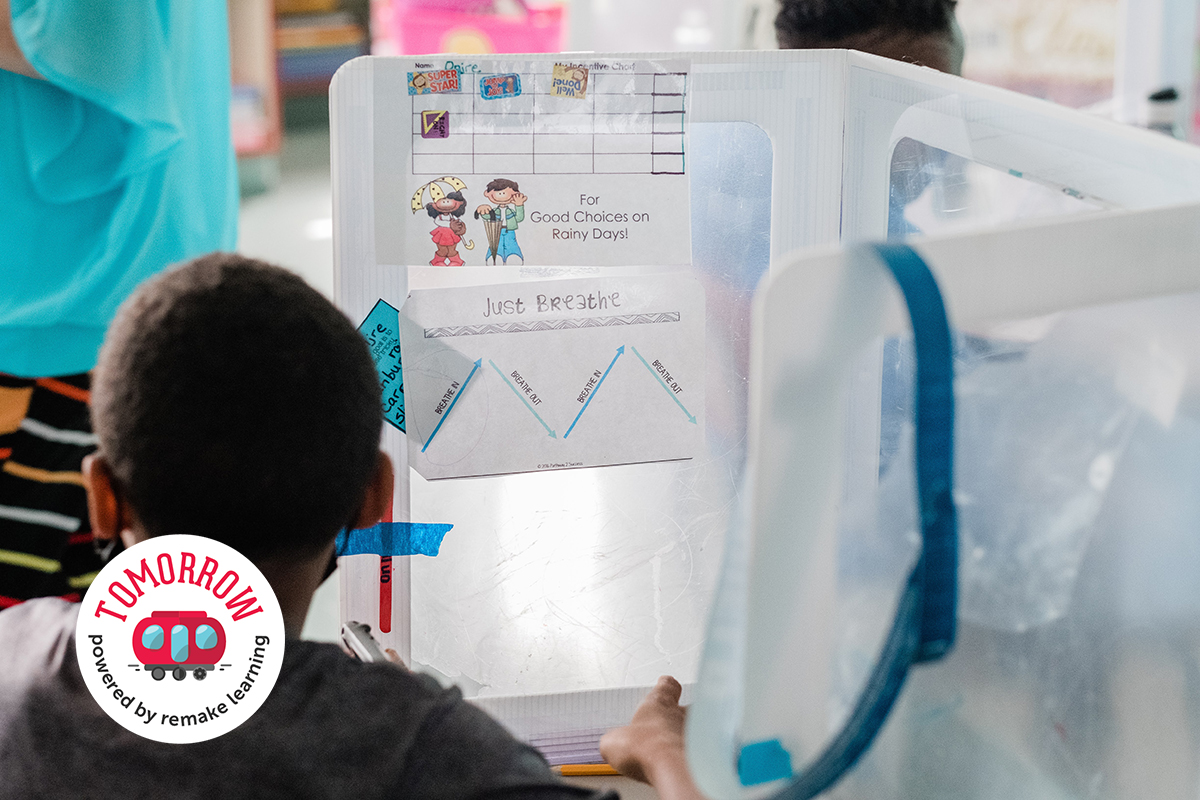

Shaw also spoke with Dr. Will Davies, director of AHN’s Chill Project, and she knew his approach could help her students. The Chill Project uses mindfulness-based exercises to equip students, teachers, and parents with a common language and shared skills to identify, discuss and react positively to stress.

The more she learned about this, Shaw says, “the more it became, ‘Why can’t we do this?’”

Community-Wide Collaboration

Until now, the answer had been a lack of funding. Clairton’s administrators care deeply about students and their families, Shaw says. But even with a supportive administration, how can you put an innovative program in place when you don’t have spare money in your school budget?

The key, as so often is the case, was collaboration.

Earlier this year, with encouragement from Davies and from Remake Learning, Shaw applied for and received a Moonshot Grant to bring systemic behavioral health to Clairton.

Through the Chill Project, “the students and every staff member—the teachers, the support staff, the paraprofessionals—we’re all learning mindfulness. We’re all taking the classes,” Shaw says.

As they learn new skills for coping with their own challenges, adults and students are also learning to understand each other better. The mindset is shifting from “what is wrong with you?” to “what has happened to you?”

There’s another benefit: This growing social-emotional knowledge helps students feel more comfortable seeking out mental health support. The district is already seeing strong demand for mental health services.

When this project was in the planning stages, Shaw says, “my first thought was ‘I hope we’re going to fill the caseload.’”

That hasn’t been a concern. A mental health therapist now works in the district five days a week, along with a supervisor for the program who also sees patients. Both are busy, and more therapists are being hired.

Data and Documentation

Clairton’s program has another component that leverages the Pittsburgh region’s learning ecosystem: Researchers from Carnegie Mellon University are documenting the work and its impact.

CMU’s research will offer solid data that can help Clairton as it continues pursuing funding and can also show other communities how they might benefit from a similar approach.

With all of this underway, Shaw is hopeful. But she isn’t slowing down her efforts to make life better for the Clairton community. Currently, she’s busy planning year two of this project, which will include bias awareness training and further support for teachers.

“I’m passionate about getting the kids what they need,” she says, “but we can’t forget teachers.”

If teachers aren’t being taken care of, she says, “then maybe they have a short fuse. Or they might end up in power struggles with the kids” that lead to disciplinary referrals where peaceful resolutions could have been possible.

Addressing this problem helps everyone.

“If teachers are not well,” Shaw says, “they can’t teach well.”