What defines something as an “innovation”? In education, what new ideas or shifts in thinking merit our attention and why? We take a closer look at what constitutes innovative practice in education, and why it matters for the future.

What is Innovation?

Something new. As John Seely Brown, formerly the chief scientist at Xerox said, “Something is innovative because it is outside of the standard.” An innovation can be a method, an idea, or a device, something that creates new value or a shift in thinking.

How does innovation apply to education today? What does it look like in education?

There are many “innovations” in today’s education landscape—teachers making minor, but critical shifts in their instructional practice to better meet the specific needs of their students; partnerships between technology companies and educators to develop instructional technology that change classroom dynamics; or communities coming together to make learning opportunities available not just in school, but in places not traditionally thought of as institutions of learning. In Kentucky, a new “Districts of Innovation” law defines innovation as “a new or creative alternative to existing instructional and administrative practices intended to improve student learning and the performance of all students.”

Driving these innovations is growing conviction that we need to rethink education’s role in a rapidly changing world, where information is at our fingertips and how we learn is more important than what we learn. “In large part,” says Seely Brown in his book, A New Culture of Learning, “the role of the teacher needs to shift from transferring information to shaping, constructing, and overseeing learning environments.” Teachers are also increasingly cultivators. “You don’t teach imagination; you create an environment in which it can take root, grow and flourish.”

What innovations—changes in pedagogical practices and shifts in thinking—merit attention?

There are numerous instructional methods and education technologies designed to advance learning innovation. These methods and technologies each have their own unique approaches and specific goals. But three foundational ideas underlie most of today’s innovations in education:

1) Interest-Driven Learning Engages Today’s Students

Kids learn best when they follow their interests. But in traditional pedagogical models, students do work based on what the community or society expects them to know and all students in a given classroom typically learn the same thing. Today some educators are moving away from this “one-sized-fits all approach” and encouraging educators to support students in interest-driven learning.

“When you can connect a passion with peers and a community that supports and motivates you,” said Collective Shift’s Connie Yowell at a recent SXSWedu conference, “and connect that to real opportunities, magic can happen.”

When you can connect a passion with peers and a community that supports and motivates you, and connect that to real opportunities, magic can happen.

With support from peers and mentors, and the time and space to create work that they find meaningful, experts like Yowell believe that interest-driven learning can lead to academic achievement, career success, and civic engagement.

For example, teen journalist Nathan Lawyer, whom we profiled in 2013, got his start making his own horror movies, shooting in the hallways of his high school with friends after school. But after dipping his toe into media production at his school’s broadcast club, and with some guidance from peers and teachers like Kris Hupp, a social studies teacher and 21st Century teaching and learning coach, Lawyer became executive director of his school’s TV channel, producing daily announcements, news, weather and live broadcasting to his peers.

“We were just having fun and goofing around, but then it turned into an actual passion,” Lawyer says.

Lawyer also learned important leadership skills and confidence that he’s taken with him into other projects. For example, he participated in This Day In Pittsburgh History, shooting on location at historical sites and museums in the region. Lawyer also traveled to South Africa over the summer to teach computer skills to local kids and visit national parks, and hopes to work in the non profit field in the future.

Cultural anthropologist Mimi Ito and colleagues have created the Connected Learning model to support passion-driven learning like Nathan’s. It rests on bringing three spheres—peers, interests, and mentors—together to support learning. These experts say that to put all young people on a path that unlocks opportunity, educators should be asking, “What are the supports each learner needs in order to achieve her potential?”

2) Learning Can Happen Anywhere, Anytime

With digital media, following one’s interests has seldom been easier. Young people can follow their nose and tap into a wealth of knowledge beyond the school walls. The internet expands access to experts, information, and others’ views, and digital tools, from iPhones to online editing software, lower the barriers to creating. Youth today can learn anywhere, anytime. The innovation lies in building vibrant learning ecosystems in communities so all young people can benefit.

“How do we make visible all the learning opportunities happening in a city 24-7 that kids are already doing?” asked Nichole Pinkard, founder of the Digital Youth Network. “How then do we help kids and their parents link to other learning opportunities they might not know about?”

If learning is now an anywhere, anytime activity that lasts our whole lives long, then the responsibility for educating today’s students needs to extend beyond the school system.

Collaboration is central to these efforts. The Remake Learning Network is part of a growing network of education innovation clusters across the country that aim to foster collaboration between diverse sectors to create more learning opportunities for its young people. Remake Learning Network is made up of, for example, more than 250 organizations, including early learning centers and schools, museums and libraries, afterschool programs and community nonprofits, colleges and universities, ed-tech startups and major employers, philanthropies and civic leaders.

3) Students Must be Able to Solve Complex Problems—to Learn How to Learn

The third shift in thinking that merits attention is a focus on 21st century skill-building.

Teaching students how to learn is as important as teaching them content.

John Dunlosky, professor of psychology at Kent State University in Ohio, in an article published in American Educator, emphasizes that “teaching students how to learn is as important as teaching them content, because acquiring both the right learning strategies and background knowledge is important—if not essential—for promoting lifelong learning.”

Today’s educators understand the need to go beyond helping students retain specific content and help them to become learners and to think like problem-solvers. These skills of critical thinking, “systems thinking,” and collaboration are often collectively referred to as 21st century skills.

Mickey McManus, chairman and principle at MAYA Design, has argued the problems facing the globe today are complex, interconnected issues, from climate change to disease management. To solve them requires a deep understanding of the interconnected nature of complex systems.

Game design is another route to build systems thinking and problem-solving skills in young people. Some educators are using Gamestar Mechanic, for example, a video game that teaches kids how to design video games in classrooms to teach skills such as systems thinking, collaboration, and iterative design.

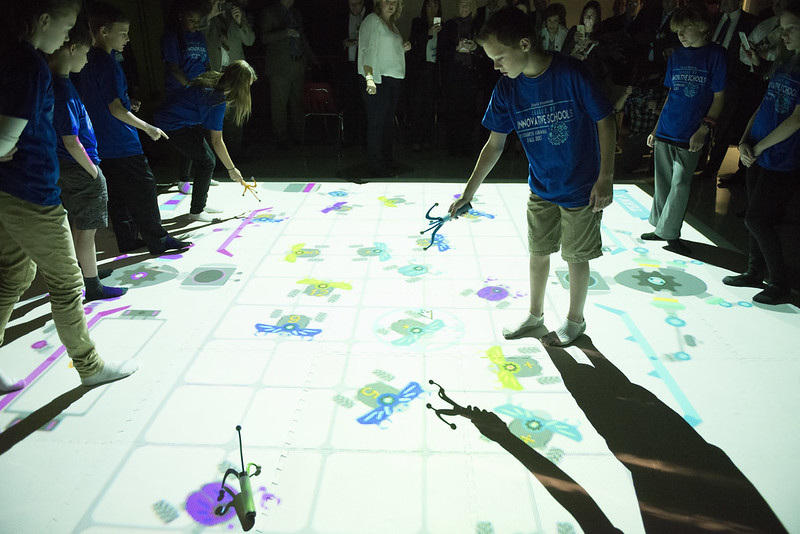

The maker movement is another way to impart 21st century skills. At makerspaces throughout the Pittsburgh region, kids can build things, tinker and experiment, and learn from their own mistakes, which also builds problem-solving and systems-thinking skills. At the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh’s MAKESHOP, for example, kids are free to experiment with wood, circuitry, a needle and thread, or old technology that they can take apart and put back together. Kids get ideas, but things usually don’t go right the first time. They’re freer to say, “Oh this didn’t work out, how can I make it work?” And importantly, they work with their peers to solve the problems.

Haven’t educators always focused on these “21st century” skills?

All of these innovative practices are facets of the fundamentals of good teaching and learning. One-hundred years ago, when philosopher John Dewey wrote about the purpose of public education, the world was also changing fast. He saw inquiry—following our interests where they lead us—at the center of education and hands-on learning as the way to experience it. Extending that philosophy to today, Gregg Behr wrote recently at Forbes, “We are now immersed in another era of great change, but our education system has not kept up. Dewey’s ideas ring truer than ever, but how do we adapt what he articulated for the modern world?”

Why act now?

Because today’s problems are more interconnected and challenging than ever, and because youth are too easily becoming disconnected from school.

In 2012, 6.7 million youth ages 16-24 were neither in school nor working. They either had dropped out of school or left with too few skills to find a job, became discouraged and disconnected from society’s twin pillars, school and work.

We are now immersed in another era of great change, but our education system has not kept up.

That drift and disconnection squashes hope and dreams for a future. More than four in ten high school dropouts ages 20-24 in 2011 were unemployed year-round. Far too many end up in the prison system, or start families before they’re ready. Others grow frustrated as door after door is shut for lack of the right credentials. Even when they do graduate, far too many students leave school without the set of skills and competencies that can lead to a good job. A recent IBM survey of more than 1,500 global CEOs revealed that it’s virtually impossible to find workers with the skills they need to do the job—because those skills don’t yet exist. Instead, CEOs are looking for employees who can constantly reinvent themselves and solve for the future.

A generation risks being lost as the demands of the world increase, and as the issues of tomorrow only get more complex. Without innovation, education may become a driver of inequality rather than the great equalizer we intend it to be.