A few years ago, Vann Williams found himself with a puzzle to solve.

A student he was mentoring had so much going for him: Athletic, outgoing, and smart. He was a quick thinker who made connections between ideas and left an impression wherever he went — often other students in the group would talk about his “beautiful eyes” whenever he was out of earshot.

But as bright as this young man was, Williams noticed he was also quick to hide his intellect. “When you got into an activity and it was time for him to answer a question,” Williams says, “instead of answering the question, he’d make a joke.”

Months passed, and Williams paid attention. He listened. Eventually, he built a connection that helped this young man unravel what it meant — and could mean — to be a “smart kid.”

The teen believed he had to choose: Keep his academic talent hidden or sacrifice his athletic image and popularity.

Without a relationship, this mystery might have gone unsolved. But once Williams and the other mentors in the group cracked the code, they encouraged the student to embrace all of his strengths.

The student realized that successful football players can bring home high grades, too, and that intellect doesn’t have to mean social isolation. Instead, it can connect learners of color to a world of opportunities and inclusivity.

HBCU Awareness and Meaningful Mentoring

Williams has been volunteering as a mentor for five years with the Consortium for Public Education. He recently joined their newest program, designed to raise awareness of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and provide mentoring to students of color.

It has two components: Each month, “there’s a virtual presentation by an HBCU to talk about their different opportunities,” says program director Gina Barrett. “Then two weeks later is the mentoring component,” which pairs three to five local professionals with a group of 10 or 12 students.

This program was the brainchild of Frank Kamara, a program manager at the Consortium, who was surprised to find that many Pittsburgh middle schoolers know little or nothing about HBCUs.

Growing up in Atlanta, he says, he and his friends learned in elementary school about the opportunities HBCUs offer, the supportive atmosphere they cultivate and the affordability of their tuition.

So the Consortium built on their experiences with “Be a Middle School Mentor,” and created this HBCU-focused program.

“The mentors don’t necessarily have to have gone to an HBCU,” Barrett says, but all the mentors are Black and brown professionals who help the students learn more about all their educational and career options.

That’s an important detail, says Stephanie Lewis, an HBCU graduate who signed on as a mentor. “Teenagers don’t always show their emotions, but they’re listening,” she says. “And it’s important for them to have adults that look like them and sound like them and are sharing their life experiences.”

Williams says it’s exciting to merge the relationship-building power of mentoring with the message that HBCUs can be a valuable path.

Along with being affordable, these colleges and universities are all about community and connection. They’re known for providing a stable and nurturing environment for those most at risk of not entering or completing college, Kamara says, including low-income students, or those who are the first-generation in their families to seek degrees.

And after graduation, HBCU alum have the opportunity to network with one another – an opportunity that can boost a young person’s career in meaningful ways.

The Consortium and the mentors are committed to sharing that information with young Pittsburghers: “I was fortunate in that I had an older sister at an HBCU and an older brother at an HBCU, so I was exposed to them in high school. And it wasn’t just the big names, like Howard, that I knew about,” Williams says.

But not all Pittsburgh kids grow up with that exposure.

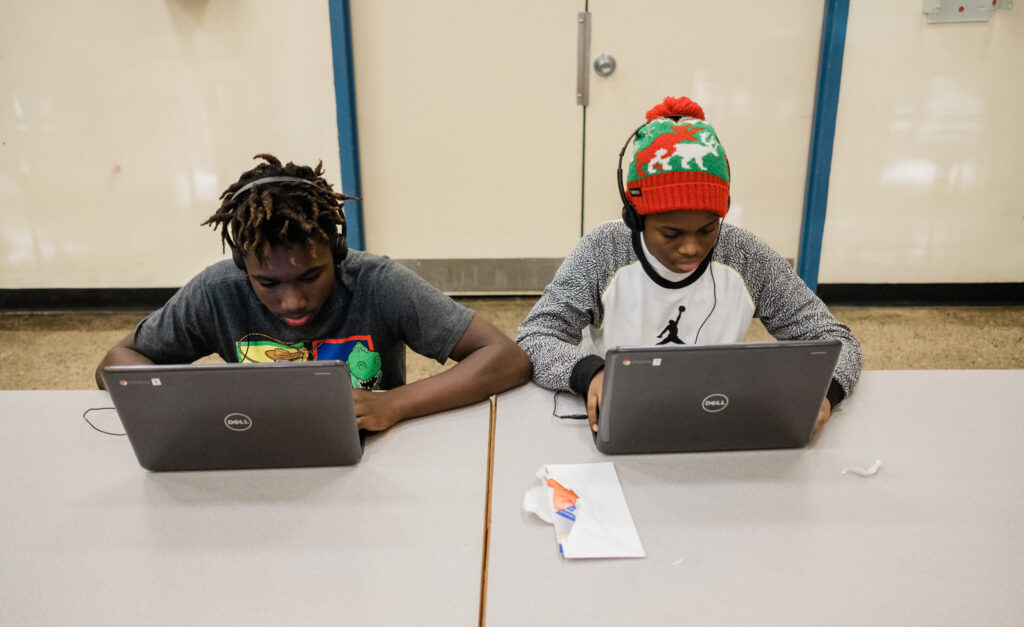

Embracing Digital Connections

The program began in November when COVID cases were rising, so it’s entirely remote for safety reasons. But that digital approach hasn’t kept students and mentors from connecting. And it has opened doors: Many HBCUs from around the country have been able to make presentations and connect with future students because they can participate without costly and time-consuming travel to Pittsburgh.

It’s a benefit for the volunteer mentors, too, including one who logs in from his home in Boston.

For Williams, an IT specialist, and Lewis, who serves as Remake Learning’s Director of Relationships, Zooming in makes these monthly sessions possible even when life is busy. “Once a month for an hour is very manageable,” Lewis says.

Williams and Lewis are both enjoying meeting the students and broadening their view of what’s possible.

The focus is on building teams and relationships, Barrett says. But in the process, the kids learn about the mentors’ careers. They also have their share of laughs.

After just a few sessions, “the students are starting to see adults as not someone that’s scary and ‘Why would they want to talk to me?'” Barrett says. “I think they’re seeing that adults are kind of like them, too.”

These solid mentoring relationships between adults and students don’t have to require big budgets or steep time commitments from mentors, and they don’t have to chew up huge amounts of students’ learning time.

But they can lead to encouragement and open new windows into all kinds of opportunities.

“We build relationships with the students,” Williams says. “Once they get a sense of the authentic you – that you’re a real person, that you have lived some of the same things they’re living right now, that you were a high school kid, a middle school kid who had issues and were able to overcome them – that stuff resonates with them.”