The first night of camping at Powdermill Nature Reserve is always the most memorable. As a dozen teenagers settle into their cabins at this environmental research center, they get their first glimpse of what it will mean to carry the title Young Naturalists for the next five weeks.

They are eager high-schoolers – summer interns excited about the chance to dive deeper into science learning but unsure what the coming weeks might bring. Many of them have never traveled this far from Pittsburgh’s city limits.

On arrival, Stephen Bucklin, a naturalist educator for the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, shows them Powdermill’s bird-banding lab. Later, during the dark of night, the adventure begins.

These students will spend the summer learning environmental science through research and stewardship. They will get comfortable with college-level STEM challenges and build friendships with kids who share their curiosity about the world around them.

But first, they see something remarkable.

“We bring in a moth expert who sets up these lights,” Bucklin says. “We’re out at night and all of these bugs are flying around. For a lot of students it’s their first time staying in a cabin in the woods. It’s kind of an immersive experience that’s more about forming relationships and building connections and building a sense of wonder – a sense of inspiration – for the remainder of the program.”

Inspiration is a key ingredient in the many pre-college STEM programs in the Pittsburgh region.

While putting math, science and engineering learning into practice, and building solid networks of peers and mentors, teens discover career pathways and take their first meaningful steps down those roads.

Over time, these programs are aiming to bring about a powerful shift toward equity and inclusivity in the worlds of STEM learning and STEM careers.

From the laboratories of UPMC’s Hillman Cancer Center and the classrooms of Carnegie Mellon University all the way to the lush landscape of Powdermill Nature Reserve and the Frick Environmental Center – Black, Latine and Indigenous learners are gaining skills and making discoveries that will help shape our world in the 21st century.

As confidence grows and networks are built, doors open. And month after month, student by student, longstanding barriers to equity are slowly, systematically being dismantled.

Building Their Futures

It’s always fascinating when Young Naturalists begin to find their career paths.

“Some of them still aren’t sure by the end of it,” Bucklin says. “But definitely a lot of them are like, ‘Oh, yeah. I think I’m getting closer to figuring out that I want to go to school for Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences,’ or whatever else they’re into that. A lot of that is a product of just being able to meet people who have different careers and hear about what they went to school for.”

As they see the varied and winding paths adults have taken, they see how they might build their own STEM careers. This is especially valuable for teens who are the first in their families to pursue a college degree.

At the same time, they begin to realize “there are other teenagers who are into this stuff, who have similar perspectives, even though they might live in a totally different neighborhood and go to a totally different school,” Bucklin says. A group messaging chat helps Young Naturalists stay in touch, and the message groups continue after the program ends.

Especially for Black, Latine and Indigenous students pursuing STEM careers, these support networks of adults and fellow teens can be life-changing.

Though the laboratories and classrooms of the CS Pathways program are different from the woods where Young Naturalists spend their summer, the excitement and inspiration can feel just as magical. And the sense of community is just as potent.

CS Pathways, part of Carnegie Mellon’s School of Computer Science, hosts a group of 30 students for four weeks each summer for a fully-funded, live-in program on campus.

From 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. – or possibly later, if challenging equations or tough problems have the group immersed – they work side-by-side with instructors and researchers on everything from computer programming to advanced math.

“The kids do a group project – their capstone project – that they present in front of their peers and in front of their instructors at the end of the program,” says the program’s senior outreach manager, Natalie Hatcher. “They’re taking what they’re learning in their core curriculum and applying it to a real world problem. So we’re really also looking at how we can use STEM to solve real-world problems.”

CS Pathways is designed for students from groups who haven’t traditionally had access to STEM careers.

“A lot of the students that we see in the program are first-generation students,” Hatcher says. “They don’t have anyone in their immediate family – a parent or guardian – who went to college. So they don’t have that life sort of modeled for them, or someone to walk them through the admissions process.”

They may also have few friends who share their passion for STEM learning.

“I can’t tell you how many times we hear students say, ‘Oh, I found my people,” Hatcher says. “We were talking just yesterday about a student who was like, ‘I didn’t tell anybody at my school. I just said I was going to camp for the summer. I didn’t tell them I was going to, like, nerd camp, basically.’ And then they get here and these kids are hanging out into the middle of the night together, coding and doing math problems.”

That sense of finding one’s people is also at play for the teens spending the summer on the other side of Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood on the University of Pittburgh’s campus. They are the Gene Team.

Breaking Down Barriers

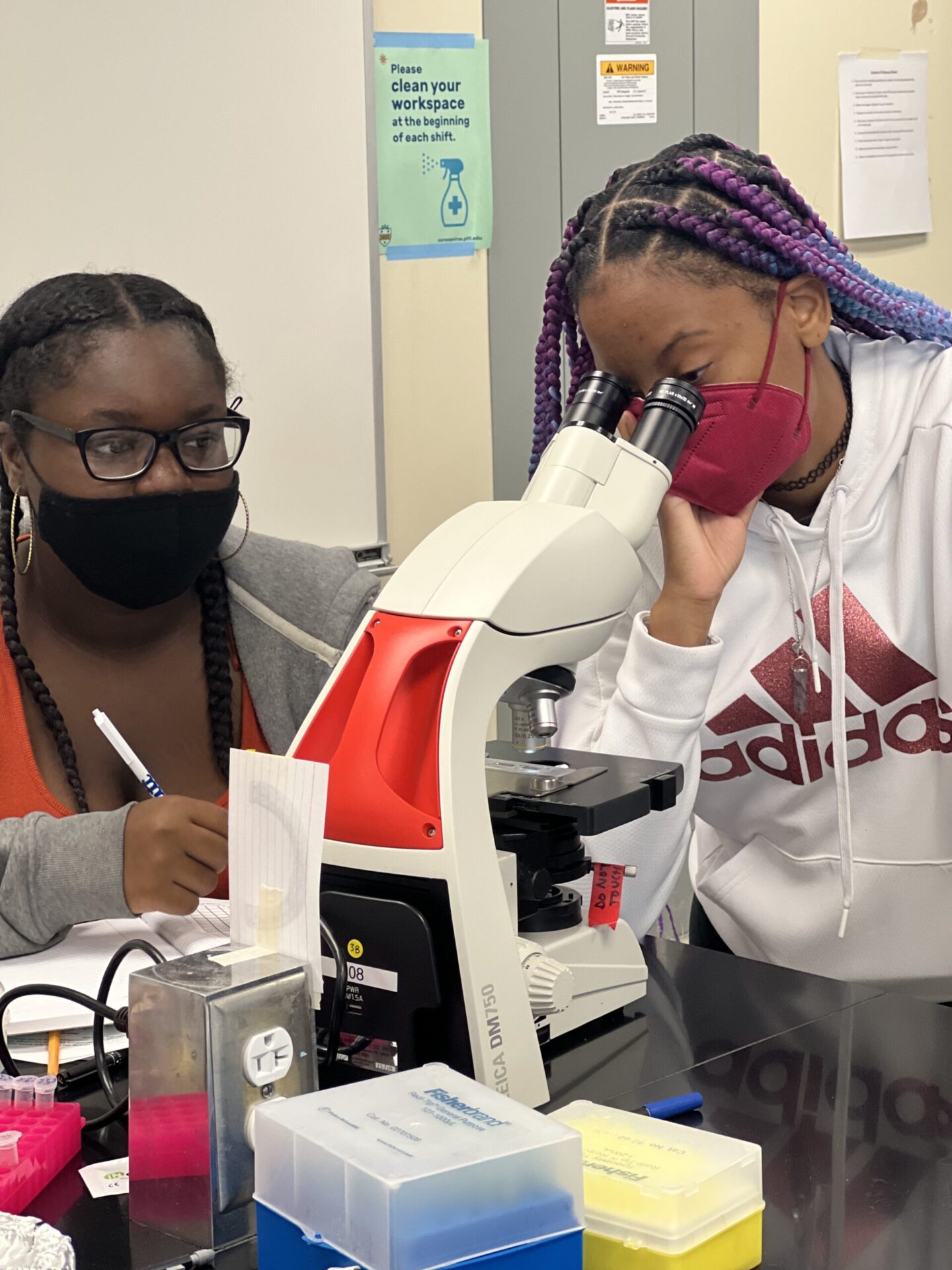

Gene Team is a summer program for high schoolers from Pittsburgh Public Schools and other urban school districts in the area. They work closely with scientists to advance the research happening in Pitt’s biology labs.

Each group tackles their own component of the research, giving students a sense of ownership of their particular piece of the project. But they share “that sense of pride in the whole team for contributing to the lab’s research,” says teaching associate professor and director of outreach Dr. Becky Gonda.

“That’s the goal from the science side of things – to advance the research,” Gonda says. “But really, we have lots of other goals outside of science: increasing the students’ critical thinking skills, problem-solving skills, experimental design, all of those types of skills that are transferable to any area in STEM, and really, in life.”

Gonda and her colleagues recruit from the city’s public schools with equity in mind.

When Gene Team began in 2006, “it was open to any student who could get here by 9 a.m.,” Gonda says. “But we decided to shift gears and say, if we really truly want to broaden participation in STEM and we know that this program is preparing students to be successful in the future, let’s focus on Pittsburgh Public students.”

Students who may be disengaged at school thrive on Gene Team. Some ask to continue working on independent projects after the summer ends, and “a pretty good amount of students end up presenting their works at the regional science fairs and winning scholarship money and lots of awards,” Gonda says. “So they’ve really not only built that sense of belonging and confidence in their science learning, but they are rewarded as well.”

That scholarship money, though, is only valuable if a student gets accepted to college.

“That’s actually how STEM PUSH kind of got started,” Gonda says. “These students were sticking around and they were knocking on my door, ‘What can we do? I want to be involved’ and then really getting attached to Pitt and then applying. And at the time, at the start of all this, none of our students of color had been accepted to Pitt.”

The reason? Sometimes their SAT scores were below the threshold. In other cases, their overall GPA or limited extracurriculars was the issue. College admissions counselors hadn’t considered that the issue might not be the student’s ability, but rather their lack of opportunity in an under-resourced school or neighborhood.

“That’s really where the frustration kind of came in. We would say, ‘we know that these students are ready for undergraduate STEM. We’ve worked with them and they’re doing this amazing work and contributing to the research at the university,” Gonda says. “Our admissions heard us and were like, ‘We agree with you, but our hands are tied. Help us.’ So that was kind of the start of the STEM PUSH work.”

Across Pittsburgh’s thriving learning ecosystem, organizations and programs are working to create an effective system of accreditation for rigorous pre-college STEM programs and support a growing number of students on this journey.

At the University of Pittsburgh’s Hillman Academy internship program, about 70% of students come from backgrounds underrepresented in STEM. Their time is spent on cutting-edge scientific research and learning about everything from writing college essays to the many paths that lead to STEM careers.

“Each student gets a mentoring team,” says Academy director David Boone. “We talk about the role of diversity in medicine, the role of diversity in education,” and “we try to bring people from lots of different backgrounds and careers and say, ‘Hey, here’s, a wide variety of careers that you could potentially have, if you continue down this path that you’re on right now.”

Former Gene Team students often move on to Hillman Academy for a new challenge.

Where Gene Team groups work together on a common project, Hillman Academy gives teens room to dive into a research project of their own along with world-class scientists.

The program is rigorous. “We start the Monday after Pittsburgh Public Schools lets out,” Boone says, and the program runs for eight weeks – nearly the whole summer – for 35 hours per week.

‘We’re based out of the Cancer Center, but we really do span most departments in the School of Medicine and then also have some faculty in engineering as well the generic sciences,” Boone says.

At one of eight research sites tackling all aspects of cancer biology, students “have a chance to do real science under the mentorship of faculty and scientists and trainees at the University of Pittsburgh,” he says.

Modeling the same approach that STEM PUSH encourages university admissions officers to take, Boone and his team choose many of their candidates based on recommendations from trusted partners like the Homeless Children’s Education Fund and Pittsburgh FAME Fund, taking a “holistic view of all the students” rather than prioritizing things like standardized test scores.

Equity is also the mission at the heart of The Citizen Science Lab, a community life sciences laboratory open to all but designed to bring hands-on STEM experiences to diverse and marginalized communities.

The Citizen Science Lab’s headquarters, a university-level lab equipped with everything from microscopes to a gene sequencer, is in Pittsburgh’s South Hills. But their programming is also offered at schools and organizations throughout southwestern Pennsylvania.

“We go everywhere,” says Chris Wandell. But “our core program is our afterschool program.”

During this grant-funded program, free for students of color, learners go to the Citizen Science Lab for two hours each week to work on long-term projects like Sea Perch. As students learn to build and manipulate underwater remotely-operated vehicles, they put basic engineering and science concepts into practice – and in many cases they fall in love with STEM learning.

Often, students who discover the Citizen Science Lab during a field trip or a brief program at their school come back for more. Last year, a student was fascinated by using DNA samples from various mammals to create a phylogenetic tree.

“This is relatively high-level DNA work and she was just an excellent student, really excited, and she came back to me and said, ‘Hey, I would really love to come back and volunteer more,’” says Wandell, “So she volunteered with us for a while and I said, ‘Hey, honestly, you’re great at all this. Do you want to have a job? Do you want to work part-time for us during school? So she’s been with us as a paid employee for just a few weeks now, but she’s doing great. This is her first job.”

These programs throughout the Pittsburgh region, which are collaborating with one another and changing the face of STEM learning, are helping young people get inspired, discover real world applications of their learning, and get opportunities that shape their successful futures.

Just like Hillman Academy interns, the Gene Team members, the CS Pathways students, and the Young Naturalists, that young employee at the Citizen Science Lab is on an incredible path. And all of these students are surrounded by inspiration.

This summer, as a new cohort of 12 Young Naturalists settle into their cabins at Powdermill Nature Reserve, they will be led by a woman named Nyjah Cephas. She is a leader of the program and a working naturalist.

But, she will tell them, she began less than a decade ago as one of them – a student intern quietly unpacking her overnight bag in a cabin in the woods, eager to spend the summer learning and growing and blazing new trails as a person of color in the world of STEM.