When the pandemic began, educators nationwide found themselves scrambling to reach their students. This was especially complicated in rural communities with no broadband service. It felt like an impossible situation: What do you do when online learning is the only option, but your students lack the infrastructure to get online from home?

You creatively adapt technology that’s been reaching people in remote places for more than half a century: broadcast airwaves.

The logic is simple. Just as broadcasting sends data to an antenna to be played on a television, datacasting uses those same signals to send data to a device connected to a computer. But while the technology for datacasting has existed for more than 20 years, it was mainly used to send out things like public safety messages–until the pandemic.

“Our stations in Pennsylvania and some of the stations around the country began thinking, ‘Could this actually be used to bridge the digital divide?’ Because at the end of the day, a television broadcast is digital,” says Ron Hetrick, President and CEO of WITF. “It’s just like sending computer files out over the air.”

Hetrick and others at PBS began talking with the Pennsylvania Department of Education (PDE) and with people at the state’s Intermediate Units, asking a vital question: How can we design a system that allows disconnected learners to receive the same content via Google Classroom or Canvas that their friends with broadband can easily access online?

They found an answer through new levels of collaboration.

“The PBS team developed a platform with input from educators, IU folks and people who are going to be using the platform on a day-to-day basis,” says Jigar Patel, coordinator of innovation and special projects at Tuscarora IU11, who has been working on the datacasting project.

“That was one of the keys when we were supporting the platform development – to make sure that it was easy for teachers to already use the stuff that they’ve developed and easily upload that to the platform to push it out,” Patel says. “They don’t have to create new materials.”

Harnessing datacasting for education was a game-changer during lockdown. But perhaps the best news is that this work is continuing and growing beyond the pandemic.

“The relationship between Pennsylvania PBS, the Intermediate Units and PDE has evolved into a lot of wonderful things,” Hetrick says.

How Does Data Casting for Education Work?

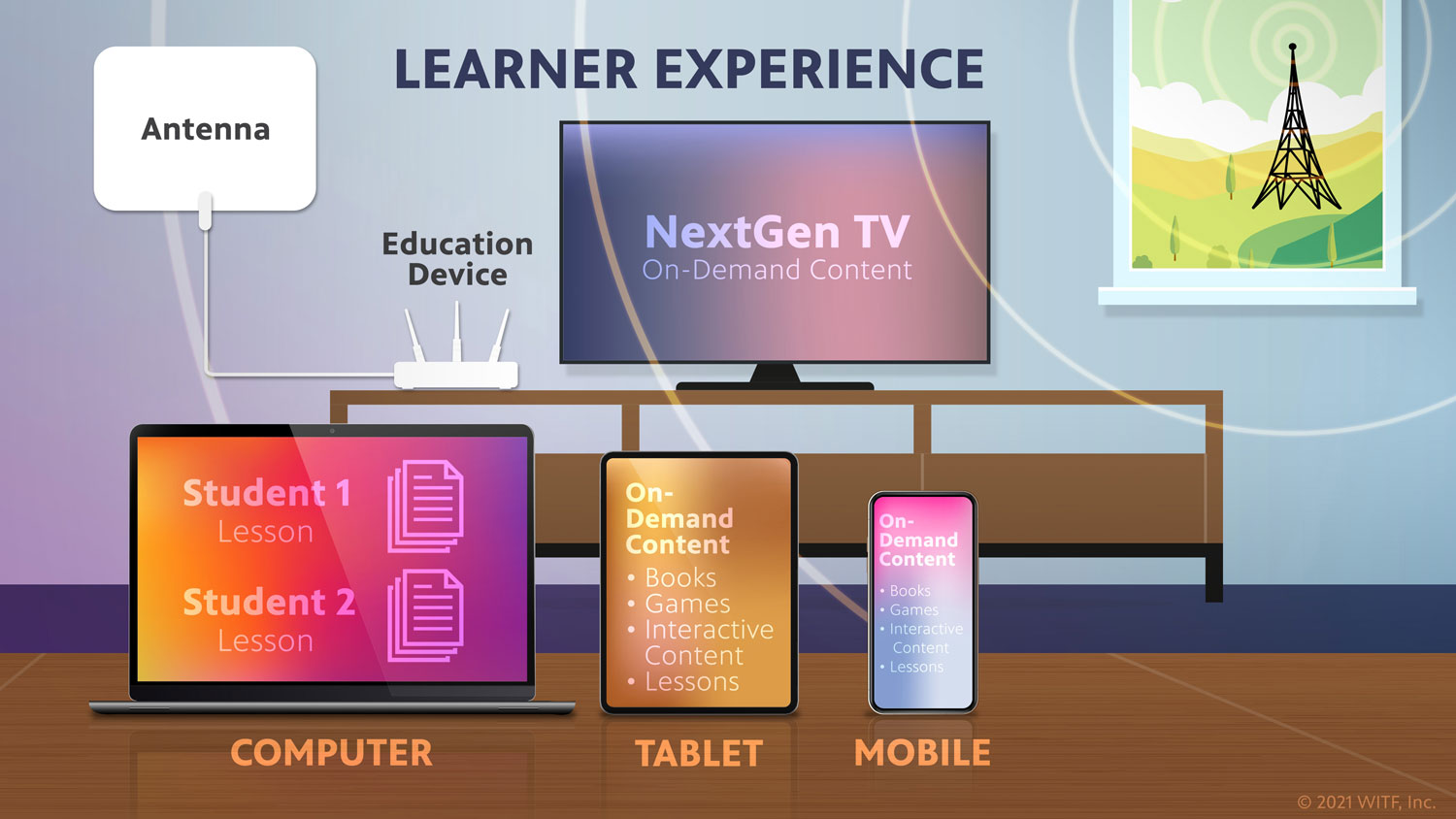

A student’s family receives a physical antenna. It might be a small antenna mounted on a window or in an attic, or a larger rooftop antenna “in a place that’s really disconnected, far away from our signal, perhaps in a valley that doesn’t have great connection,” Hetrick explains.

That antenna connects to a small device that receives secure broadcasts from the child’s teacher. “The information that the teacher broadcasts to individual students is cached on that device,” Hetrick says, “and then they actually log into that device with any wireless device that they have in the home, whether that’s an iPad, a Chromebook, a laptop.”

It creates what he describes as an “offline internet environment, but in an area that doesn’t have access to broadband. So they’re actually getting the PowerPoints, the Word files and videos. Any assets that they would have in school, they could have at home.”

In homes with multiple learners, a single datacasting device can serve all of them. Each student logs in with their own email address and sees their personal dashboard. “As soon as they sign in, they see content that was pushed out to them,” Patel says, and the student can interact with that content as though they were online.

That’s the key: Although datacasting uses broadcast airwaves, all students aren’t receiving the same broadcast. They are accessing their school’s learning management system, where the content is personalized to them.

“Within Google Classroom, they’re already doing some of the differentiation of learning,” Patel says. Teachers simply upload that personalized content, “and then they push it out to the individual student.”

That was a priority as the system was being developed: “One of the big challenges we went through is teachers not having enough time to develop individualized learning for an offline student versus an online student,” he says. “What the PBS team has done is they’ve built in the functionality to connect things like Google Classroom and Canvas.”

Equitable Access Ahead of Progress on Broadband

Although schools have reopened in the wake of the pandemic, rural learners in remote locations remain hampered by a lack of internet access at home, and that isn’t likely to change soon.

“At the end of the day, we all want children and families to have access to broadband affordably and equitably,” Hetrick says. But even with public support, installation of that infrastructure in remote areas is likely years away.

“This allows you to bridge that gap now,” Hetrick says, in the “period of time until we can actually get to the most disconnected people, get to those last-mile people. To be able to help those families over the long term is a really great thing.”

In areas without broadband, “kids still need access to resources when they go home,” Patel says. “If they don’t have access to YouTube when they go home like other kids do, or if they’re doing homework, and they want to look up a concept, it’s not easy for them to do that.”

Through datacasting, he says, “we can push out content that’s relevant to them, that might be helpful to them in doing their work after school. So there’s still a big need. … And this fills that resource gap.”

Patel says the datacasting team has also begun connecting rural learners with public library resources in Pennsylvania. “Libraries are great resources,” he says, but rural students may lack the transportation to get there. “They need a parent to take them there, and the parent might be working.”

Datacasting can give those students access to audiobooks, e-books and more.

The Power of Partnership

When the pandemic began, the PDE “asked us to reimagine learning,” Hetrick says. “Basically, they said, let’s push the extent of what’s possible, recognizing that what learning will look like coming out of the pandemic will be different than what we thought about it going in.”

That request might never have happened under different circumstances.

“I don’t think we would have partnered with PBS and have had that strong partnership develop, if it weren’t for the pandemic,” Patel says. “Even though our ideas align in terms of what we’re trying to do, we never had an opportunity to be in the same space together.”

This pandemic-era solution is now evolving in unexpected ways: Incarcerated learners at places like York County Prison and Lancaster County Prison are now learning via datacasting.

The team is also developing learning kiosks that are powered by datacasting. They will be used in public health spaces around the state. And Hetrick says an upcoming partnership is expected to bring datacasting to early education spaces like daycare centers, giving preschoolers access to interactive games and learning activities.

The PDE is also looking to use datacasting for adults seeking workforce training.

“We have a lot of people who are trying to do workforce development to get career skills, who are in rural areas of the state,” Hetrick says. Currently, “they’re driving 40 miles to get educated and to have access to the internet and do these things.”

With datacasting, “they can have access to the curriculum. And without necessarily driving an hour and a half per night, they could actually advance their skillset. So it’s happening on the youth and early ed side, and it’s also on the adult side, to give these disconnected places real opportunity.”

The project has even grown to include a nonprofit called the Information Equity Initiative that’s bringing this work beyond Pennsylvania to other PBS stations across the country and internationally, in Mexico and several countries in the Caribbean and Africa.

“This all has been incubated here with help from Jigar and our friends at the other IUs, and our other PBS colleagues,” Hetrick says. “It’s been really great to work together and develop this framework.”