Over recent decades, rapid technological advances have changed how young people learn and experience the world. However, these advances also help expand our understanding of the brain and childhood development.

I recently had the opportunity to talk with Dr. Judy Cameron, Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh and one of the co-founders of the Brain Architecture Game, a tool that teaches people about the lasting effects of early childhood experiences on the brain.

Through our conversation, Dr. Cameron shared how her work informs early childhood development while relating to educational policy and the science of learning–for both children and adults.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Erin Gatz (EG): The Brain Architecture Game was originally created as a way to talk about childhood trauma to legislators in a hands-on way. Can you share more about its origin and purpose?

Dr. Judy Cameron (JC): Its origins began with The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child and the Harvard Center on the Developing Child. The council and the center work together to drive science-based innovation that achieves breakthrough outcomes for children facing adversity. We’re trying to understand how experiences that children have shape their brain development as much as the genes they inherit.

A main focus of the council and the center is to translate information about experiences and brain development to social service providers, pediatricians, child-care providers, educators, and legislators. We want to create greater support for policies and resources that will provide all children with strong, positive brain-building experiences. You can access our materials for free at developingchild.harvard.edu.

Around 2012, many council members were regularly giving talks at state legislatures, and we noticed a correlation between the timing of our visits and subsequent voting on childhood resource bills: If we visited not long before a vote, legislators frequently voted in favor of allocating resources. But, if several weeks went by between our visit and a vote, results were more variable.

We hypothesized that legislators were not absorbing the information we shared well enough to immediately recall the issues. We needed a strategy to get legislators to understand and use the information they were being told, so they would easily recall it for a longer period of time, and be more likely to support resource votes.

EG: That seems like quite a challenge, though.

JC: Exactly! How do you get very busy legislators to really learn new scientific information?

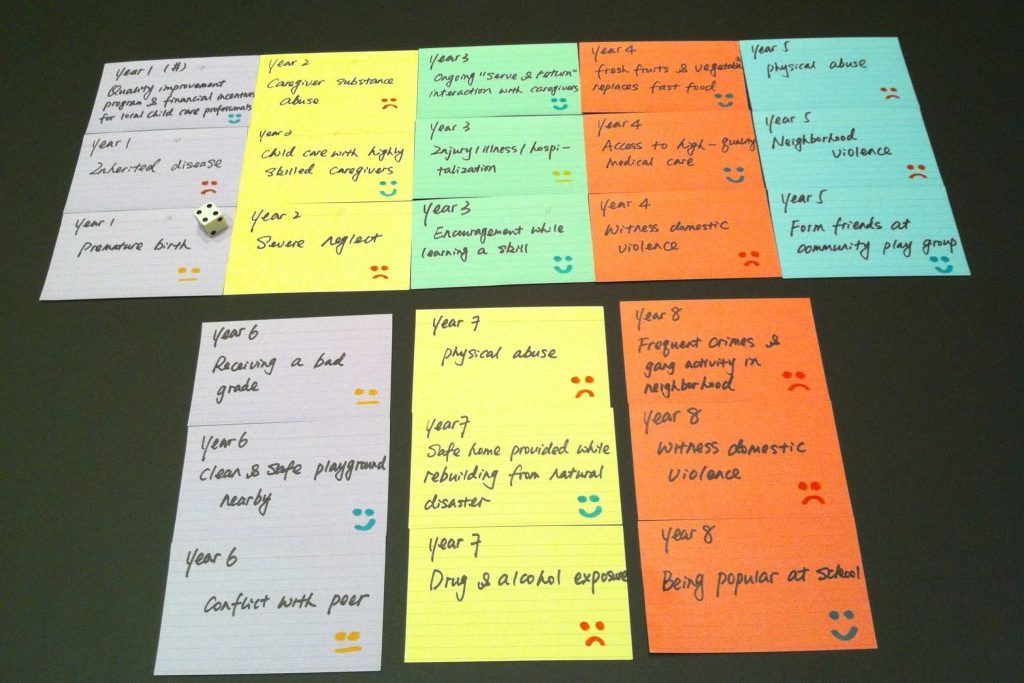

We needed a strategy that was engaging, fun, and took a limited amount of time. In collaboration with developer Marientina Gotsis, from the Interactive Media & Games Division of the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California, a small team of council members and I developed The Brain Architecture Game to show how life experiences impact brain development. It can be played by small groups of 4-8 people in about an hour. We have now played this game with thousands of professionals, including legislators, and have found that the game is a fun, engaging way to effectively teach them about the importance of experiences and social supports in shaping children’s brain development.

EG: Where can we find the game today?

JC: You can purchase the game at thebrainarchitecturegame.com. In 2020, we developed a Remote Teams Edition, which allows play by groups working together via videoconference. It’s available at play.thebrainarchitecturegame.com.

EG: How does the game benefit educators and the relationships they have with youth? What impacts have you seen?

JC: In 2017, my research group started a program to provide the same information about children’s brain development to the general public, including parents and adults living in stressed communities. This educational program is marketed at low cost through Working For Kids Building Skills LLC.

Working For Kids focuses on teaching adults how to facilitate sturdy brain development in children using hands-on activities, games, and storytelling. Unlike our previous work with professionals, this work is specifically designed for teaching adults who prefer learning-by-doing.

Post-game assessments show that adults learn, among other things, how important they are in developing childrens’ brain circuits when they are “plastic,” or very sensitive. The plastic period for different brain circuits varies; for some, it’s only after birth or until the early years of life, while others remain plastic up to 25 years. To support the best brain development, adults need to learn when children should be using different parts of their brain. They need to be creative and engage children in activities that are fun and rewarding. This will strengthen the development of specific brain circuits. The Brain Architecture Game teaches this information in an engaging manner, so adults remember it and can use it to better facilitate sturdy brain development in children.

EG: You have an incredibly varied background as a professor of psychiatry, neuroscience, reproductive sciences, clinical and translational science, as well as behavioral and community health sciences. What motivates you to translate your work for educators?

JC: I have spent much of my career studying the brain mechanisms by which experiences change how the brain works – by making new connections between neural circuits, activating specific genes in the brain, strengthening some brain circuits and weakening others. I am still doing this work, but as we have accumulated more and more data showing how very important experiences are in strengthening children’s brain development, I have become convinced that for mankind to solve the problems of the future, we absolutely need to make sure children have experiences that allow them to build the strongest brains possible.

We have to share our science with the public and make sure all children benefit from what we have learned. Educators play a central role in this very important mission. They are in a position to influence large numbers of children and also to educate their parents. To be effective, educators have to be creative and very “person-centered,” so that they can figure out how to best reach each child and motivate them to do activities that will strengthen their brain development. Because educators play a pivotal role in the lives of children, Working For Kids has focused much of its attention on providing resources to teachers (from early preschool to high school) to help them engage children in activities that will strengthen brain development.

EG: Is there anything else you would like to share about the Brain Architecture Game or any of your other work?

JC: The Brain Architecture Game has been so effective over the last decade that Working For Kids has focused attention on developing new games, like The First Pathways Game. This game features more than 250 age-appropriate activities that adults can do with children ages 0-8 to strengthen brain circuits for language skills, motor skills, problem-solving, social emotional regulation, early science learning, and math skills. Activities use easy-to-find household materials and include a narrator and video demonstration. There are customizations available for children with developmental delays and versions of the game for in-classroom educators, you can contact us at info@workingforkids.com for more on that.

We have also recently developed new, interactive “visual novels” for adolescents, to help strengthen their decision-making skills. Teens can access these on their phones, available both as a free android and iOS app.

The first game is called “Abingdon High.” Readers become a character in the story, joining a group of other teens at school the week before homecoming. As the novel progresses, they must make decisions about social events, school work, interactions with teachers and parents, after school jobs, and problems they and their peers are having. The novel proceeds in different directions depending on the decisions the reader makes. This is a fun, engaging way to get teens to strengthen the brain pathways underlying decision-making skills. And as with our other games, we have curricula that have been designed for use by educators in the classroom (again, contact us at info@workingforkids.com for more).

Join Erin and Dr. Cameron on May 19 from 12 – 1:30 pm for a virtual Lunch & Learn and learn to play the Brain Architecture Game! RSVP here.