The greater Pittsburgh region is home to more than 150 makerspaces, with schools, libraries, and after-school programs that provide area students with maker opportunities.

That has many questioning whether all students will receive the same access and resources. Equitable access and diversity—along many different lines—have come to the forefront of many ongoing discussions within the maker movement.

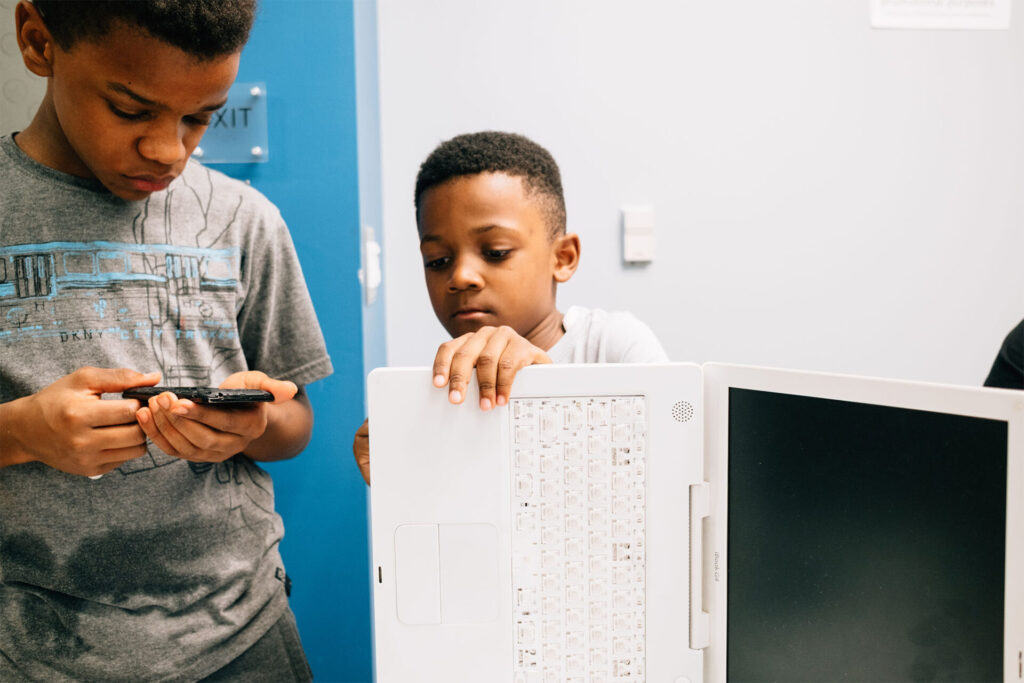

Based in the Homewood-Brushton YMCA, the Y Creator Space is an after-school program for children ages 9 to 13. Program Director Alexandra Rice estimates that the population the Y Creator Space serves is almost 100% African American. Most students are from Homewood and attend schools in the area, where the median income ranges from $14,000 to $21,000 and 81 percent of students are considered economically disadvantaged.

“We see a lot of kids with a ton of potential,” said Rice. “They get concepts and ideas quickly, but that is not always manifested in their schoolwork.”

At nearby Westinghouse Academy 6-12, by one recent estimate, more than 90% of eighth-grade students ranked below proficient in science and reading, and only 3% of eighth-graders were rated proficient or advanced in math. Part of the aim of Y Creator Space is to help students develop skills and confidence in STEM subjects.

“We’re hoping to create an environment where they feel they’re supported and can learn to conduct themselves in society in a way that is going to lead to their success across all areas,” said Rice.

Social and emotional skills like grit, confidence, and the ability to make multiple attempts at solving a problem are also among the lessons Y Creator Space seeks to teach participants.

The program strives for equitable access to making by providing students with a range of entry points, addressing each of what Rice calls “the three Cs”: casual, connected, and committed.

While many programs operate on a committed basis, asking students to pledge to a certain level of attendance, this can often weed out kids who are unable to commit for reasons beyond their control, such as an unstable home life.

“You miss a lot of kids that way,” said Rice. From 3 to 5 p.m., the space is open for self-directed projects, homework, or even social time.

Participants have the right, but not the obligation, to use the space, and are free to leave whenever they choose during this open time. By offering students a casual entry point, Rice hopes to draw them in, ultimately getting them to participate at a deeper level.

After dinner is served in the evening, the program offers “club time”—ongoing group projects—to connected students. For those willing to commit to attend at least 70% of meetings over a 10-week period, there is STEM Studio, which Rice describes as a “deep dive” into a particular topic. One recent Studio topic was game design, with a faculty member from Carnegie Mellon University’s Entertainment Technology Center working with students.

Funding is a constant challenge for the program, which is offered for free. Many funders gravitate toward supporting new and innovative programs rather than existing ones, Rice said.

“Funding support for existing, successful programs is critical,” said Rice. “These are programs that already have an established base of participants and who have figured out how to deliver effective programming to their audience. If we are serious about equitable access to Makerspaces and STEM programs, we need continued support from the funding community and other generous donors because we are working in neighborhoods where families cannot financially contribute to these programs themselves.”

Defining Diversity

Kyle Murphy, a Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh teaching artist, helps run makerspace activities at Wilkinsburg’s Hosanna House, a multi-purpose community center that strives to give children active learning experiences. Along with a co-teacher, Murphy offers a summer camp that serves approximately 150 kids and an after-school program serving about 80 kids, about two-thirds of whom are African-American, from the underserved community of Wilkinsburg.

For Murphy, diversity can significantly impact the way that educators define makerspaces and present these spaces to their audiences.

“There’s this idea that a makerspace is 3-D printers and it has to be equipped with a certain level of technology,” Murphy said. “A makerspace could literally just be a space with scissors and some donated art supplies. It’s not things or stuff, it’s a mindset and a set of values.”

At Hosanna House, much of the maker programming centers on fiber arts—sewing and weaving—and electronics, featuring activities such as disassembling donated electronic items.

“Making isn’t that new, actually,” Murphy said. “Attaching it to its historical roots is important, and attaching a utility or a purpose to it for a particular community.”

In the case of sewing and weaving, Murphy pointed out the social component of these kinds of making activities, which allow for conversation as kids work on their projects.

“A big component of diversity that’s often missing is creating a space to allow for needs to be filled,” said Murphy, “rather than pushing a certain agenda or certain kinds of content.”

Recognizing Gender Diversity

Equitable access to people of all genders is also an important part of the broader conversation around diversity.

Prototype PGH, a feminist makerspace focused on providing maker opportunities to women, emerged from conversations between Erin Gatz and Louise Larson at TechShop.

“Something that makerspaces do really well is bring in a diversity of fields,” said Larson. “Where there’s room for improvement is in who has agency in those fields. If you don’t already operate in a STEM field and you come into a maker or STEM environment, how do you have agency in that space?”

With the help of a grant from The Sprout Fund, Gatz and Larson opened their own studio space in North Oakland in order to increase access to women, in particular low-income women. The goal is to create sustainable community growth while also thinking about what that means in terms of individuals growing, building new skills, and changing careers.

Beyond simply offering tools and training to Prototype’s more than 150 members, the organization strives to create a network that extends well beyond the studio. Community partners like the Good Peoples Group and 1Hood Media have presented in Prototype’s workshop series and used its 3-D printing equipment, respectively.

Prototype has also expanded its reach across the city, offering workshops at the Ujamaa Collective in the Hill District and Chatham University’s Women’s Business Center, among others.

“We’re taking a slow-growth approach to expanding our network, but that’s one of our motivating forces,” said Gatz. “The idea of a network is influential in our thinking about what Prototype can be and how we’re prototyping the city and networking support.”

Acknowledging Diverse Settings

Diversity of setting can be easy to overlook when considering access to makerspaces. But rural schools can often struggle to provide their students with the same resources accessible to those living in urban areas.

Lou Karas, Director of Center for Arts & Education at West Liberty University, outside of Wheeling, West Virginia, works with educators from a variety of communities to provide students with making opportunities.

Many of the educators she works with are based in school districts with a single elementary, middle, and high school.

“When you have a teacher or librarian interested in making, they may not know of others working in that space,” Karas said. While rural schools often face a lack of resources, isolation from a broader making community can also pose a formidable challenge.

“Teachers in rural school districts look at the sophisticated makerspaces in other areas and say, ‘We’ll never be able to do that,’” Karas said. She finds it important to point out the process those schools followed to build their maker programs, from applying for grants to, most importantly, starting slowly and building on small successes.

Drawing on the community for both resources and support is also critical. In communities where parents may work in technology fields, there may be an external demand for makerspaces and fabrication labs. But in areas where parents have less technological experience, teachers and administrators may need to work to achieve the interest and enthusiasm necessary to create support for maker programming.

Karas suggested that schools could offer evening workshops on the different uses for their equipment and technology for the community. By building broad interest and engagement in making, they might gradually build support for making in the school district.

Other teachers seek community buy-in by emphasizing the maker movement’s links to crafts that are popular and well-established within the community.

“Woodworking and quilting are also forms of making,” Karas said. Drawing those connections can build community support and can also inform teachers’ lesson plans in meaningful ways.

“There’s no ‘one size fits all’ for makerspaces,” she added.

Last two photos: Peter Leeman. All other photos: Ben Filio Photography